The great circus performer known as Charles Blondin was born as Jean-François Émile Gravelet near St. Omer in France on 28th February 1824. His father, André Gravelet, was himself a tightrope walker as well as a veteran of Napoleon's grande armée. From the age of five, when he became spellbound watching a group of visiting entertainers, Jean-François wanted to be a tightrope walker. After receiving tuition from a former sailor, he convinced his parents to enrol him at the École de Gymnase, the famous school for acrobats in Lyon. Within months he made his professional début as "The Little Winder" and at the age of seven appeared before the King of Sardinia in Turin.

The great circus performer known as Charles Blondin was born as Jean-François Émile Gravelet near St. Omer in France on 28th February 1824. His father, André Gravelet, was himself a tightrope walker as well as a veteran of Napoleon's grande armée. From the age of five, when he became spellbound watching a group of visiting entertainers, Jean-François wanted to be a tightrope walker. After receiving tuition from a former sailor, he convinced his parents to enrol him at the École de Gymnase, the famous school for acrobats in Lyon. Within months he made his professional début as "The Little Winder" and at the age of seven appeared before the King of Sardinia in Turin.

Tragically he became an orphan when he was only ten-years-old and after finishing his schooling he found a surrogate families in the circus troupes he travelled around Europe with for the next eighteen years. In 1851 he joined the Ravel Family of acrobats with whom he travelled to the United States to work for the leading circus impresario of the age: Phineas T. Barnum. While sailing across the Atlantic, Blondin (as he was now known) saved the life of a young nobleman who fell overboard during a storm.

In 1858, three years after arriving in America for the first time, Blondin conceived the feat that was to make his name: crossing the Niagara Falls on a tightrope. He planned the stunt meticulously but still had convincing his agent and prospective investors of the feasibility of the plan. Nevertheless, in spite of not being able to cross at his preferred location but with the support of a local newspaper, the Niagara Falls Daily Gazette, and a small amount of financial backing, he finally set a date for his exploit.

In the late afternoon on 30th June 1859, Charles Blondin stepped out on to the three-inch-wide, 1100-foot-long rope which spanned the falls 160 feet above the water. Between 10,000 and 25,000 spectators watched on as he carried his 30-foot-long 40lb balancing-pole to the middle of the rope, where he had a lie down and a drink from a bottle that he hoisted up from a boat moored below. He then completed the crossing. In all the spectacle lasted around seventeen minutes to the acclaim of the crowds. As the bands on both sides of began to pack up, he announced that would make a return journey, which he completed in around seven minutes.

Blondin crossed the Falls many more times, always with some sort of gimmick to attract the crowds: carrying a passenger; cooking an omelette half-way across; crossing on stilts. His celebrity status achieved, Blondin, his wife, and their five children toured the world making a fortune with his act before returning to Great Britain, which he became a subject of in 1868. Following some sort of financial disaster he was forced out of retirement in 1880 and his last performance was in Belfast in 1896 when he was seventy-one years of age. He died of diabetes the following year and was buried in Kensal Green

The Niagara Falls Public Library web site has a number of images of Blondin available from their Historic Niagara Digital Collections.

Related posts

First ascent of Mont Blanc, 8th August 1786

First man swims across the English Channel, 24th August 1875

First crossing of the English Channel in an autogyro, 18th September 1928

Customised search for historical information

30 June 2009

On this day in history: Blondin crossed Niagara Falls on tightrope, 1859

29 June 2009

On this day in history: Cisalpine Republic created, 1797

In April 1792, France declared war on Austria beginning the French Revolutionary Wars, which lasted until 1802. Following initial defeats, the French army started to make gains against the coalition of nations that opposed them, in part due to the institution of the levée en masse (mass conscription) but also due to the tactical skills of the French generals. In 1796, one general in particular made a name for himself with a series of victories in northern Italy: Napoleon Bonaparte.

In April 1792, France declared war on Austria beginning the French Revolutionary Wars, which lasted until 1802. Following initial defeats, the French army started to make gains against the coalition of nations that opposed them, in part due to the institution of the levée en masse (mass conscription) but also due to the tactical skills of the French generals. In 1796, one general in particular made a name for himself with a series of victories in northern Italy: Napoleon Bonaparte.

Following decisive victories at the Battle of Montenotte over the armies of Sardinia and Austria, and the defeat of the Austrians at the Battle of Lodi, Bonaparte captured Milan and Mantua. The Papal forces had little choice but to sue for peace, which he accepted in February 1797. With no belligerents left in northern Italy, Napoleon was free to take his army into Austria, but before he did so he created a two republics in captured territories as client states of France - the Cispadane Republic to the south of the River Po, and the Transpadane Republic north of the river. These republics comprised part of the Republic of Venice, the Romagna, the former duchies of Milan, Modena, and Parma, along with the Papal legations of Bologna and Ferrara

On 29th June 1797, Bonaparte merged the province of Novara with these two republics to form the Cisalpine Republic, which, although nominally independent, was effectively ruled from France. The promulgation of a constitution the very next month created a republic that followed the French model: they adopted the Republican calendar; the territories were divided up into departments; a minority of the populace elected representatives to two councils who chose an executive. Nevertheless, the commander of the occupying French forces retained ultimate authority. By the end of 1797, the Austrians had capitulated and signed the Treaty of Campo Formio by which they recognised the legitimacy of the Cisalpine Republic.

The fate of the Republic became intimately linked to that of its founder. Following his seizure of power in France, the Cisalpine Republic became the Italian Republic in 1802, with Bonaparte as its President. The year after Napoleon became Emperor of the French he added Venetia to the Republic to create the Kingdom of Italy and took the crown for himself. The Kingdom was broken up by the Congress of Vienna after his final defeat in 1815.

If you wish to learn more about Bonaparte and the Cisalpine Republic, Project Gutenberg has a copy of John Holland Rose's The Life of Napoleon I (London, 1910)

Related posts

Napoleon escaped from Elba, 26th February 1815

Prince Murat executed, 13th October 1815

28 June 2009

On this day in history: Battle of Berestechko begins, 1651

In the mid-seventeenth century, one of the largest and most populace states in Europe was the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth (also known by the rather the delightful name of Most Serene Commonwealth of the Two Nations). This elective monarchy extended from Poznan in the west to Smolensk in the east; it included Latvia and much of modern day Estonia, Belarus and Ukraine. As such the Commonwealth's population consisted of many ethnic groups, not all of whom were content to be ruled by a Polish-Lithuanian monarch.

In the mid-seventeenth century, one of the largest and most populace states in Europe was the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth (also known by the rather the delightful name of Most Serene Commonwealth of the Two Nations). This elective monarchy extended from Poznan in the west to Smolensk in the east; it included Latvia and much of modern day Estonia, Belarus and Ukraine. As such the Commonwealth's population consisted of many ethnic groups, not all of whom were content to be ruled by a Polish-Lithuanian monarch.

In 1648, a number of ethnic groups within the Ukraine rebelled against the Roman Catholic King John II Casimir. Initiated by Cossacks the war of liberation soon attracted their fellow Orthodox Christians: Ukrainian peasants and Crimean Tatars. The rebels - commanded by Bohdan Khmelnytskyi, a Zaporozhian Cossack who gave his name to the uprising - managed to drive the Polish nobles, Catholic priests, and Jewish leaseholders from their land in the first few months of the insurgency - massacring those who did not flee. Meanwhile, the King was building an army to take back the Ukraine.

On 28th June 1651, the largest battle of the seventeenth century began when approximately 140,000 rebels engaged just over 50,000 Commonwealth soldiers under the command of the king at Berestechko in the western Ukraine. The battle lasted for three days by the end of which between forty- and seventy-thousand rebels lay dead (including women and children at their camp), while the Polish-Lithuanian army had lost less than one-thousand men. The rebels were forced to capitulate and signed the Treaty of Bila Tserkva on 28th September.

In spite of the defeat, Khmelnytskyi (aka Chmielnicki) had not given up hope of forcing the Commonwealth out of the Ukraine, but he realised that he needed allies to do so. Initially he approached the Ottoman Sultan who offered the rebels vassal status; however, the Ukrainians were not keen on a Muslim overlord. So it was that Khmelnytskyi signed the Treaty of Pereyaslav in 1654, making the Ukraine a vassal state of the co-religionist Russian Tsar, finally ending Polish-Lithuanian domination of the Ukraine.

Related posts

Ivan the Terrible crowned Tsar, 16th January 1547

Foundation of Saint Petersburg, 27th May 1703

27 June 2009

On this day in history: First electronic Automatic Teller Machine installed, 1967

In 1939 the Armenian-American inventor Luther George Simjian came up with the idea of a automated mechanical cash dispenser for banks. He registered twenty payments for his invention and finally persuaded the City Bank of New York (now Citibank) to run a six-month trial of one his machines; however, lack of customer demand resulted in the removal of the meachine. According to Simjian, "It seems the only people using the machines were a small number of prostitutes and gamblers who didn't want to deal with tellers face to face."

In 1939 the Armenian-American inventor Luther George Simjian came up with the idea of a automated mechanical cash dispenser for banks. He registered twenty payments for his invention and finally persuaded the City Bank of New York (now Citibank) to run a six-month trial of one his machines; however, lack of customer demand resulted in the removal of the meachine. According to Simjian, "It seems the only people using the machines were a small number of prostitutes and gamblers who didn't want to deal with tellers face to face."

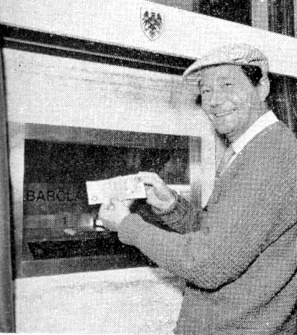

The idea was revived in the 1960s by the Scottish inventor John Shepherd-Barron, who apparently came up with the idea while in the bath. While considering ways in which he could have access to his money anywhere in the world, he realised that he could create a vending machine for money. When he approached Barclays Bank with his idea they jumped at the chance.

On 27th June 1967 the world's first electronic ATM came into service at Barclays' Enfield Town branch, in North London. The first customer to use the machine was the actor Reg Varney, most famous for his roles in situation comedies. On this pioneering system, the customer inserted a cheque impregnated with the slightly radioactive carbon 14 which the machine detected and then dispensed an envelope containing a ten pound note. One year prior to the installation of Shepherd-Barron's machine, another Scottish inventor called James Goodfellow patented the Personal Identification Number (PIN) technology, which is used on ATM machines around the world today.

Related posts

First European banknotes, 16th July 1661

First banknotes issued in America, 3rd February 1690

Bank of England founded, 27th July 1694

Also on this day in history

Czech reformist manifesto published, 1968

26 June 2009

On this day in history: First Victoria Crosses presented, 1857

During the state opening of Parliament in 1854 Queen Victoria praised her forces currently engaged in the Crimean War leading Capt. G.T. Scobell, M.P, to suggest...

During the state opening of Parliament in 1854 Queen Victoria praised her forces currently engaged in the Crimean War leading Capt. G.T. Scobell, M.P, to suggest...

[...] that an humble address be presented to Her Majesty to institute an 'Order of Merit' to be bestowed upon persons serving in the Army or Navy for distinguished and prominent personal gallantry during the present war and to which every grade and individual... may be admissible.

In March 1855 the Government announced that such an order of merit would be instituted. Queen Victoria herself had a role in approving the text of the Warrant and the design of the medal, which was finally settled upon in March 1856. Mr C.F. Hancock, a London jeweller, was given the appointment to produce 106 specimens. The medal was to be made from the bronze of Chinese cannons seized from the Russians at the siege of Sebastopol in 1855 (although analysis confirms that through the years different sources of metal have been used).

The first presentation was made in Hyde Park on 26th June 1857 where Queen Victoria decorated 62 servicemen for showing valour "in the face of the enemy" during the Crimean War. The first recipient was Commander Henry Raby RN who was recognised for his part in rescuing a wounded soldier while under fire during an attack on the Redan on 18th June 1855. Fourth in line was Charles Davis Lucas, a mate in the Royal Navy who, three years earlier, had thrown a live shell overboard after it landed on deck of his ship, the HMS Hecla. This act of bravery was the earliest to have been rewarded with the medal. The VC remains the highest military decoration awarded in the United Kingdom.

The Victoria Cross Society website includes a biography of Charles Lucas on its page of sample journal articles.

Related posts

Queen Victoria`s first train journey, 13th June 1842

25 June 2009

On this day in history: First doctorate conferred on a woman, 1678

On 25th June 1678, the University of Padua conferred the first ever doctorate on a woman: Lady Elena Lucrezia Cornaro-Piscopia. She was born in the Palazzo Loredano, Venice, on 5th June 1646 to John Baptist Cornaro-Piscopia, Procurator of San Marco, and his wife Zanetta Giovanna Boni. At the age of seven Elena began her studies under the mentorship of the Aristotelian John Baptist Fabris. Fabris persuaded Elena's father to do all he could to further his daughter's education. Having the money and influence to do so he recruited Professor Alexander Anderson of Padua, Professor Luigi Gradenigo - the librarian at San Marco, and other tutors to school Lady Elena in a variety of disciplines. She became fluent in at least seven languages, including ancient Greek and latin, and because of this became known as Oraculum Septilingue. She also studied mathematics, astronomy, philosophy and theology - the latter two being her favourites.

On 25th June 1678, the University of Padua conferred the first ever doctorate on a woman: Lady Elena Lucrezia Cornaro-Piscopia. She was born in the Palazzo Loredano, Venice, on 5th June 1646 to John Baptist Cornaro-Piscopia, Procurator of San Marco, and his wife Zanetta Giovanna Boni. At the age of seven Elena began her studies under the mentorship of the Aristotelian John Baptist Fabris. Fabris persuaded Elena's father to do all he could to further his daughter's education. Having the money and influence to do so he recruited Professor Alexander Anderson of Padua, Professor Luigi Gradenigo - the librarian at San Marco, and other tutors to school Lady Elena in a variety of disciplines. She became fluent in at least seven languages, including ancient Greek and latin, and because of this became known as Oraculum Septilingue. She also studied mathematics, astronomy, philosophy and theology - the latter two being her favourites.

In 1672 Lady Elena's father sent her to the University of Padua to complete her studies. Initially she had no intention of attaining academic qualifications, rather she simply wanted to continue learning. Nevertheless, because of her father's insistence and in spite of the resistance of some academics and churchmen, who would not permit a woman to become a Doctor of Theology, she was eventually allowed to prepare for the examination for Doctor of Philosophy with Professor Carlo Rinaldini as her tutor.

Six years later, the Cathedral in Padua hosted the public ceremony in which Lady Elena received the doctoral insignia: the laurel wreath placed on the head; the ring on the finger; and the ermine cape over her shoulders. In attendance were the professors of the University of Padua, invited academics from the Universities of Bologna, Ferrara, Perugia, Rome, and Naples, as well as other notable scholars and many of Venetian politicians.

Elena turned her back on the life of privilege and devoted herself to charitable works, becoming a Benedictine oblate. On 26th July 1684, eight years after receiving the doctorate, and at only thirty-eight years of age, Lady Elena Lucrezia Cornaro-Piscopia died of what is believed to have been tuberculosis. The whole city of Padua mourned the loss of this remarkable woman who continues to be remembered: a year after her passing the University of Padua struck a special medal in her honour; a statue of her still stands outside the University; and further afield, Vassar College, New York, has a stained glass window that depicts her presenting her thesis on that day Cathedral of Padua when she became the first woman to receive a doctorate.

Related posts

First university founded in Americas, 12th May 1551

First university inaugurated in Australia, 11th October 1852

First higher-education institute in Texas opened, 4th October 1871

24 June 2009

On this day in history: Münster Rebellion ended,1535

In the sixteenth century a number of increasingly vocal critics of the practices and beliefs of the Catholic church emerged. These criticisms, taken as a whole, became known as the Protestant Reformation, the effects of which were felt across Europe as new churches emerged. Switzerland, in particular, was a hotbed of religious reform being birthplace of Calvinism and the Anabaptist faith, although some historians maintain that the latter also had roots in Holland and the Rhineland.

In the sixteenth century a number of increasingly vocal critics of the practices and beliefs of the Catholic church emerged. These criticisms, taken as a whole, became known as the Protestant Reformation, the effects of which were felt across Europe as new churches emerged. Switzerland, in particular, was a hotbed of religious reform being birthplace of Calvinism and the Anabaptist faith, although some historians maintain that the latter also had roots in Holland and the Rhineland.

The Anabaptists were so called because they deferred baptism until somebody is old enough to chose to enter the faith. Not only did Anabaptists want religious reform but also formed a social reform movement, which became increasingly radicalised during the Peasants' War, a series of popular revolts that flared up across the Holy Roman Empire in 1524 and 1525. The princes and bishops restored order, re-established the status quo, and in some places, they made conditions even harsher for the common people, many of whom were radicalised and so became Anabaptists.

One place where the seeds of radical religious and social reform took root was the German of Münster. Ruled by a bishop, Franz von Waldeck, and council of guild leaders, the citizens looked to religious leaders to bring about social change. The Anabaptist pastor Bernhard Rothmann declared that a new prophet would soon arrive to liberate the people of the city. This 'prophet' was a Dutch baker called Jan Matthys, who along with Rothmann and Jan Bockelson, a tailor from Leyden, whipped up such religious sentiment within the populace that in February 1534 they managed to drive the council and bishop from the city and install their own mayor, Bernhard Knipperdolling, a guild leader and Anabaptist convert.

In Easter of that year, Matthys set out to conquer the rest of the world believing that the Day of Judgement was at hand, but he and his thirty followers died at the hands of the bishop's besieging army. Bockleson took over as religious and political leader and instituted a number of social reforms including the legalisation of polygamy and instituting the community of goods. He claimed to be a descendent of King David and as such was the absolute ruler of the new 'Zion'.

Nevertheless, this new 'Zion' was not to last. On the night of 24th June 1535, the bishop's forces finally gained entry to the city using information gained from Heinrich Gresbeck, who had been a guard on the city walls and was captured while trying to flee. The bishops forces quickly took the city, capturing the Anabaptist leaders and killing almost all of the male population. Bockelson and Knipperdolling were tortured and eventually executed in January 1536, their mutilated bodies were displayed in cages hung from the steeple of St. Lambert's Church, which are still there today.

The Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopaedia Online has a more detailed account of the Münster Anabaptists.

Related posts

The Solemn League and Covenant, 25th September 1643

Louis XIV revokes the Edict of Nantes, 22nd October 1685

23 June 2009

On this day in history: The Antarctic Treaty came into force, 1961

On the 15th October 1959 representatives of the twelve countries met in Washington D.C. to negotiate a treaty regarding the future of Antarctica. The twelve nations - Argentina, Australia, Belgium, Chile, France, Japan, New Zealand, Norway, South Africa, the Soviet Union, the United Kingdom and the United States - were those that had undertaken scientific activity on the frozen continent during the International Geophysical Year, which lasted from July 1957 to December 1958. Poland requested to join the negotiations, having sent some scientists to the Russian Antarctic station, but this request was denied since they could sign the proposed treaty at a later date.

On the 15th October 1959 representatives of the twelve countries met in Washington D.C. to negotiate a treaty regarding the future of Antarctica. The twelve nations - Argentina, Australia, Belgium, Chile, France, Japan, New Zealand, Norway, South Africa, the Soviet Union, the United Kingdom and the United States - were those that had undertaken scientific activity on the frozen continent during the International Geophysical Year, which lasted from July 1957 to December 1958. Poland requested to join the negotiations, having sent some scientists to the Russian Antarctic station, but this request was denied since they could sign the proposed treaty at a later date.

In the fifteen months prior to the conference, working groups had met to do much of the groundwork in a climate of cooperation that was uncommon during the Cold War. The spirit of compromise extended into the treaty negotiations. On 30th November the representatives announced that they had reached agreement on all fourteen articles of the treaty. These articles, which applied to all land and ice shelves below 60 degrees south latitude, included a ban on weapons tests on the continent, an undertaking to share scientific information, a guarantee of free movement in the area, and the empowerment of the International Court of Justice to settle and disputes.

On 1st December 1959, the treaty was opened for signatures. The governments of the twelve original nations each ratified the treaty. Chile was the last to do so, signing the treaty on the day that it came into force, 23rd June 1961. Since then representatives of thirty-four other nations have also signed the treaty.

The website of the Office of Polar Programs at the U.S. National Science Foundation includes the complete text of the 1959 treaty.

Related posts

Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty signed, 1st July 1968

22 June 2009

On this day in history: Caribbean immigrants arrive on the Empire Windrush, 1948

The Second World War had left the United Kingdom with a labour shortage, just when it needed as many workers as possible for the task of reconstruction. To alleviate this shortage the Royal Mail Lines placed an advertisement in the Jamaica's Daily Gleaner newspaper in April 1948. The advertisement offered a ticket Kingston, Jamaica to England for only £28 and 10 shillings on the ex-German troopship Empire Windrush, which was due to dock in the Caribbean on its journey from Australia back to the Britain.

The Second World War had left the United Kingdom with a labour shortage, just when it needed as many workers as possible for the task of reconstruction. To alleviate this shortage the Royal Mail Lines placed an advertisement in the Jamaica's Daily Gleaner newspaper in April 1948. The advertisement offered a ticket Kingston, Jamaica to England for only £28 and 10 shillings on the ex-German troopship Empire Windrush, which was due to dock in the Caribbean on its journey from Australia back to the Britain.

Many of the 492 people that took up this offer were ex-servicemen - mostly from the Royal Air Force - who either hoped to rejoin the RAF or wanted to take up the promise of work and a better life in their "mother country". Many Britons were not pleased at the thought of immigrant workers, and Parliament debated the matter while the ship was crossing the ocean. Nevertheless, many of the passengers had served during the war for "King and Country" and all carried British passports, so there was no legal cause to turn them away.

On 24th May 1948, the Empire Windrush set sail on her month long journey across the Atlantic, which ended on 22nd June when she docked at Tilbury in Essex. On arrival, just under half of the West Indians received temporary accommodation at the Clapham South deep shelter in London - built as an air-raid shelter during the war beneath the underground railway station.

Over two hundred of them found work straight away, mostly in the newly instituted National Health Service and with London Transport. The nearest labour exchange (office where they could find work) was in nearby Brixton, an area where many of them found homes, bestowing upon that area its multi-racial heritage.

During the Parliamentary debates on immigration, the politicians who promoted imported labour suggested that the workers that the foreign workers would only stay for a short while, and indeed many of the West Indians thought the same. Nevertheless, many chose to stay and raise families in their new home. The journey of the Empire Windrush marked the beginning of a new - and as is often the case, troubled - era of multiculturalism in Britain.

The BBC History website has a number of pages devoted to the Empire Windrush generation, including the memories of some of the ship's passengers.

Related posts

Foundation of first permanent British colony in the Caribbean, 28th January 1624

Emperor Haile Selassie visited Jamaica, 21st April 1966

21 June 2009

On this day in history: Mechanical reaper patented, 1834

In the early nineteenth-century, a Virginian called Robert Hall McCormick spent his time developing various inventions on his farm in Rockbridge County. In 1831, he passed the development of one such invention, a mechanical reaper, to his son, Cyrus, who was still in his early twenties but showed an aptitude for business. Cyrus improved upon his father design and received a patent for the McCormick Reaper on 21st June 1834. The machine required only two men to operate it: one rode the horse that pulled the machine; the other raked the cut grain from the platform on which it collected. In one day two men using the reaper could cut as much grain as over a dozen men working with scythes.

In the early nineteenth-century, a Virginian called Robert Hall McCormick spent his time developing various inventions on his farm in Rockbridge County. In 1831, he passed the development of one such invention, a mechanical reaper, to his son, Cyrus, who was still in his early twenties but showed an aptitude for business. Cyrus improved upon his father design and received a patent for the McCormick Reaper on 21st June 1834. The machine required only two men to operate it: one rode the horse that pulled the machine; the other raked the cut grain from the platform on which it collected. In one day two men using the reaper could cut as much grain as over a dozen men working with scythes.

In spite of the labour-saving potential of the machine, initials sales were not promising; by the end of 1846 he had sold fewer than one hundred machines. Undaunted he moved to Chicago, the following year, where he found success by using original marketing techniques - such as sending out trained salesman to demonstrate the machines - and by benefiting from the city's status as an industrial centre and railway hub, which aided manufacture and distribution. Not long after relocating his brothers, William and Leander, joined him as partners in the McCormick Harvesting Machine Company.

The McCormick's continued to develop the machine, as well as other farming machinery, which they sold around the world. Sales undoubtedly benefited from the awards and honours bestowed upon Cyrus and his machine: the reaper won a gold medal at the 1851 Great Exhibition, in London; and the French Academy of sciences elected Cyrus as a corresponding member.

Cyrus died in 1884, passing the company to his grandson Cyrus Hall McCormick III. It was he who, two years later, presided over the darkest event in the company's history: the Haymarket Affair of 4th May 1886. Nevertheless, the McCormick's company went from strength to strength, staying at the forefront of the manufacture and sale of not only farming equipment but also non-agricultural vehicles, weapons, and domestic appliances.

You can download a pdf copy of the original 1834 patent document from pat2pdf.org.

Related posts

First recorded sale of friction matches, 7th April 1827

Elisha Otis installed his first passenger elevator, 23rd March 1857

Blue jeans patented, 20th May 1873

Edison patented the phonograph, 19th February 1878

First gasoline-driven automobile patented, 29th January 1886

Vacuum cleaner patented, 30th September 1901

20 June 2009

On this day in history: The Tennis Court Oath, 1789

On 5th May 1789 the Estates General of France met at Versailles for the first time in 175 years to ratify various proposed reforms that the King's ministers hoped would end the financial crisis that France found itself mired in. Rather than discuss the new taxes, the representatives of the third-estate were more interested in discussing the organisation of the Estates General. Their concern was that whilst they represented the vast majority of the nation, the other two estates - the clergy and the nobility - would vote together against them since each estate only had one vote.

On 5th May 1789 the Estates General of France met at Versailles for the first time in 175 years to ratify various proposed reforms that the King's ministers hoped would end the financial crisis that France found itself mired in. Rather than discuss the new taxes, the representatives of the third-estate were more interested in discussing the organisation of the Estates General. Their concern was that whilst they represented the vast majority of the nation, the other two estates - the clergy and the nobility - would vote together against them since each estate only had one vote.

Attempts at diplomacy between the estates failed, and on 17th June the representatives of the third-estate - by then calling themselves les communes ('the commons') - and a number of delegates from the other two estates who had joined them renamed themselves the National Assembly. They defiantly declared that that since they represented most of the French people then national sovereignty resided with them; although, initially at least, they still recognised the authority of King Louis XVI whose consent they would seek in order to pass any new laws.

Louis, however, was not about to be dictated to. Rather, on 19th June, he chose to go to the National Assembly, annul any degrees it had made, command the clerical and noble delegates to return to their respective orders, and then draw up popular legislation to bring the third-estate back into the fold. He ordered that the hall in which the National Assembly met be locked and a guard be placed there to prevent them meeting while he met in session with leading courtiers to plan how to proceed.

Consequently, on 20th June 1789 the National Assembly found itself without a place to meet. The delegates commandeered an indoor-tennis court that was close by. Once gathered inside, the recalcitrant deputies took a collective oath in defiance of the King to continue meeting until an acceptable constitution be established for the French nation. This act of unity and defiance that consolidated the revolution enjoyed widespread popularity in France. As a result Louis had little choice but to order the remaining delegates of the first- and second-estate to join the National Assembly.

The History Guide site has a page with the full text of The Oath of the Tennis Court.

Related posts

Meeting of the French Estates-General, 5th May 1789

Feudalism abolished in France, 4th August 1789

Parisian women bring Louis XVI back to Paris, 6th October 1789

France reorganised into 83 départements, 4th March 1790

Paris celebrates la Fête de la Fédération, 14th July 1790

Guillotine used for first time, 25th April 1792

September Massacres begin, 2nd September 1792

Louis XVI executed, 21st January 1793

19 June 2009

On this day in history: Rosenbergs executed, 1953

In 1936 Julius Rosenberg met Ethel Greenglass through the Youth Communist League. They both lived in New York and came from working-class Jewish families. Three years after their first meeting they were married. That same year Julius gained a degree in electrical engineering from the City College of New York.

In 1936 Julius Rosenberg met Ethel Greenglass through the Youth Communist League. They both lived in New York and came from working-class Jewish families. Three years after their first meeting they were married. That same year Julius gained a degree in electrical engineering from the City College of New York.

Following the United States' entrance into the Second World War, Julius joined the Army Signal Corps and worked on radar equipment. A year later, in 1943, the Rosenbergs stopped publicly endorsing communism and cancelled their subscription to the Daily Worker, the newspaper of the Communist Party USA. Nevertheless, the pair were still in contact with leading American communists through whom they made the acquaintance of Alexandre Feklisov, a Soviet spy.

By chance, in 1944 Ethel's brother, David Greenglass, started working on the United States' nuclear weapon programme, the Manhattan Project. Towards the end of that year, the Rosenbergs allegedly persuaded him to pass technical details of the programme to the Soviets to help them also develop a nuclear weapon. According to Feklisov, Julius also recruited a number of other people with access to information on top secret projects to spy for the Russians.

In early 1950, British Intelligence arrested Klaus Fuchs, another scientist working on the Manhattan Project, on charges of espionage. Eventually, the trail of spies and couriers led back to David Greenglass and the Rosenbergs, all of whom were arrested. In January 1951, the US Grand Jury indicted the three of them and the trial of the Rosenbergs began in March that year. Following a guilty verdict on the charge of conspiring to commit espionage, the presiding Judge, Irving Kaufman, sentenced them both to death. Greenglass, who testified against his sister and brother-in-law, received a fifteen year sentence, of which he served ten years.

On 19th June 1953, a special session of the US Supreme Court finally dismissed requests for a stay of execution. So, that evening, first Julius and then Ethel were executed by electrocution at the Sing Sing Correctional Facility at Ossining, New York. They left behind two orphaned sons, Robert and Michael, who were finally adopted by the songwriter Abel Meerpol - famous for writing the Billie Holliday song 'Strange Fruit' - and his wife Anne. Controversy still surrounds the Rosenberg's (particularly Ethel's) role in the spy ring, as well as their trial and execution.

The University of Missouri-Kansas City School of Law host a complete transcript of the Rosenberg Trial on their website.

Related posts

Sir Walter Ralegh beheaded, 29th October 1618

First execution in Salem witch trials, 10th June 1692

Last hanging at Tyburn gallows, 3rd November 1783

Guillotine used for first time, 25th April 1792

Louis XVI executed, 21st January 1793

Prince Murat executed, 13th October 1815

18 June 2009

On this day in history: First Europeans sighted Tahiti, 1767

In August 1766, the Royal Navy frigate HMS Dolphin set sail under the command of Samuel Wallis, on her second journey of discovery and circumnavigation. Following victory in the Seven Years' War, three years earlier, the Royal Navy hierarchy decided to explore the Pacific Ocean in order to develop new trade routes and possibly find a new route to the all-important East Indies. Hence Commodore John Byron's journey of circumnavigation, on the Dolphin, which was the first to be completed in less than two years.

In August 1766, the Royal Navy frigate HMS Dolphin set sail under the command of Samuel Wallis, on her second journey of discovery and circumnavigation. Following victory in the Seven Years' War, three years earlier, the Royal Navy hierarchy decided to explore the Pacific Ocean in order to develop new trade routes and possibly find a new route to the all-important East Indies. Hence Commodore John Byron's journey of circumnavigation, on the Dolphin, which was the first to be completed in less than two years.

In Dolphin, Wallis knew he had a ship that was up to the task; however, he would be accompanied on his voyage by HMS Swallow, a sloop that was far from ship-shape, under the command of Philip Carteret. The two ships became separated after sailing through perilous Straits of Magellan. In spite of the decrepit condition of his craft, Carteret managed to complete his mission arriving back in England three years after setting sail, having discovered various new landmasses including Pitcairn Island and a series of atolls that now bear his name.

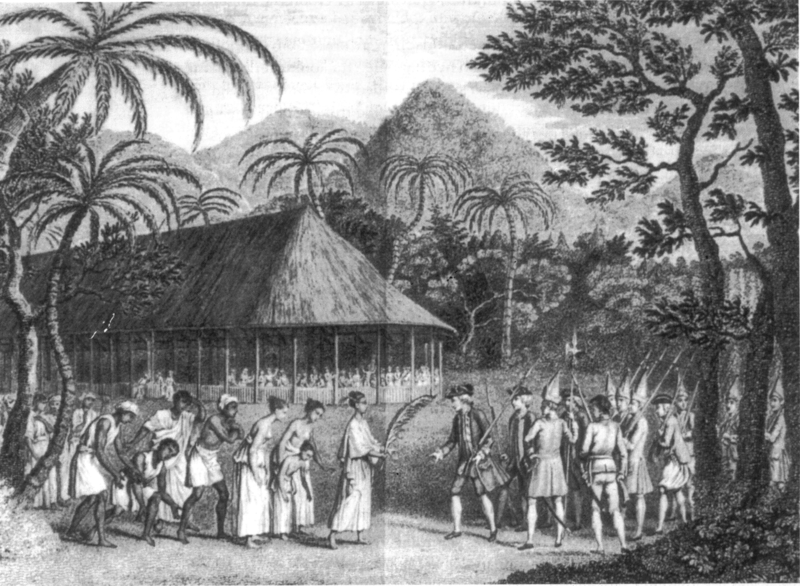

After losing contact with the Swallow, Wallis directed his crew to sail across the South Pacific; but scurvy and ill favoured winds forced him to head northwards. In the warmer seas he also discovered a number of islands then unknown to Europeans and on 18th June 1767 he sighted Tahiti, where the Dolphin and her crew remained for the next five weeks. In the first few days saw sporadic attacks by Tahitians on the crew, but these stopped after many locals were injured or killed by cannon fire.

Wallis could do little to quell the disturbances because he had been stricken with fever even as the health of his men improved. Indeed, when the Dolphin returned to England in May 1768, her commander's health was still in a poor state in spite of his efforts to maintain the health of his crew by using a three shift rotation so that the sailors could have more rest, maintaining stores of fruit and vegetables, and by keeping clothes and bedding as clean and dry as possible - innovations that were all used by the famous Captain Cook during his voyages of exploration.

To learn more about the voyages of Byron, Cateret, Wallis and Cook the National Library of Australia's web site hosts a hypertext version of John Hawkesworth (Ed.), Account of the Voyages ... in the Southern Hemisphere (London, 1773), Vol 1 and Vol 2 & 3

Related posts

First European landing on New Zealand, 18th December 1642

HMS Beagle launched, 11th May 1820

17 June 2009

On this day in history: Mumtaz Muhal died, 1631

On 17th June 1631, the third wife of the Islamic ruler of India, the Mughal Emperor Shah Jahan, died during childbirth. Mumtaz would probably have been lost to posterity had it not been for the mausoleum that the Emperor had built in her honour. One of the greatest buildings of the world and a testament to love: the Taj Mahal.

On 17th June 1631, the third wife of the Islamic ruler of India, the Mughal Emperor Shah Jahan, died during childbirth. Mumtaz would probably have been lost to posterity had it not been for the mausoleum that the Emperor had built in her honour. One of the greatest buildings of the world and a testament to love: the Taj Mahal.

Mumtaz Muhal was born Arjumand Banu Begum in April 1593. Her father was a Persian noble and brother of the wife of the Emperor Jahangir. At the age of fourteen she was betrothed to marry Prince Khurram Shihab-ud-din Muhammad, but the court astrologers delayed their marriage for five years until the most conducive date for a happy marriage in 1612.

Whether by craft or coincidence the astrologers were proven right: the couple were inseparable. Arjumand - now renamed Mumtaz Muhal ('Chosen One of the Palace') - accompanied Khurram on his travels across the Mughal Empire even travelling with his entourage on some of his military campaigns. After ascending to the Peacock Throne in 1628, Prince Khurram - now Shah Jahan ('King of the World') - gave Mumtaz his imperial seal, because he loved and trusted her so.

Three years later, while accompanying her husband on a campaign in the Deccan Plateau, Mumtaz went into labour in the town of Burhanpur but died during the birth of their fourteenth child, a daughter called Gauhara Behum. According to contemporary accounts Shah Jahan was heartbroken: he mourned in solitude for a year after which he emerged a broken man. He set about having a tomb built that would be a suitable memorial to their love. The result was the Taj Mahal in Agra.

The plinth and tomb took twelve years to build, and further buildings were added over the next ten years. Following the completion of the Taj Mahal, Shah Jahan's third son by Mumtaz, Aurangzeb, seized power and confined him to the nearby Agra Fort. When Jahan died, eight years later he was interred alongside his beloved Mumtaz.

Related posts

Shri Swaminarayan Mandir inaugurated, 24th February 1822

16 June 2009

On this day in history: First woman in space, 1963

Immediately after the Soviet Union's success in putting the first man into space in 1961, the head of cosmonaut training on the Russian space programme, Nikolai Kamanin, suggested to his superiors that it was their patriotic duty to again beat the Americans by being the first to put a woman into space. Chief Designer Korolev agreed and in October 1961 the search began for likeable woman who was an avowed Communist with experience of parachuting - piloting skills were not required as the Vostok spacecraft flew automatically. Five women received the call to train as cosmonauts, including Valentina Vladimirovna Tereshkova, a textile worker and daughter of a war hero.

Immediately after the Soviet Union's success in putting the first man into space in 1961, the head of cosmonaut training on the Russian space programme, Nikolai Kamanin, suggested to his superiors that it was their patriotic duty to again beat the Americans by being the first to put a woman into space. Chief Designer Korolev agreed and in October 1961 the search began for likeable woman who was an avowed Communist with experience of parachuting - piloting skills were not required as the Vostok spacecraft flew automatically. Five women received the call to train as cosmonauts, including Valentina Vladimirovna Tereshkova, a textile worker and daughter of a war hero.

The five women began the exhaustive period of training and testing: centrifuge rides; isolation tests; rocket theory; parachute jumps; piloting jet fighters, physical exercise; and, weightless flights. In spite of being the least qualified - the other four had received higher education, and included engineers and test pilots - Tereshkova faired better in front of the Communist selection board than the other finalist, Valentina Ponomareva, who had excelled in all the other tests. Since the flight was essentially a propaganda exercise, Korolev nominated Tereshkova, and Premier Krushchev - who had the final say - agreed.

On the morning of 16th June 1963, Vostok 6 launched from Baikonur Cosmodrome in Kazakhstan with the call sign "Seagull". While in space Tereshkova kept a log and took photographs, while the ground staff monitored her physical condition. Controversy surrounds the flight: some reports claimed that she became emotionally distraught, and she certainly vomited during the flight; however, the flight lasted longer than initially intended leaving her nothing to do with no support from the ground staff; she claimed that rather than the weightlessness it was the poor food she had been given that made her sick; and - as was later confirmed - she noticed that there had been an error in the automatic orientation of the capsule, which the ground crew confirmed and corrected.

Tereshkova's ordeal did not end until she safely returned to earth. After ejecting out of the capsule during its final descent (as all cosmonauts did) she noticed that she was parachuting towards lake that was to large for her to swim to the edge of in her state of exhaustion. Fortunately the wind blew her back over dry land. Nevertheless, from a propaganda point of view the mission was a complete success. Tereshkova's flight had a longer duration than all the American space-flights, thus far, put together. She was also significantly younger than all the NASA astronauts. The Soviet hierarchy quashed any attempts to discredit her, whether based in fact or chauvinism.

After the flight, Tereshkova married another cosmonaut, Andrian Nikolayev (an event which was again used for propaganda purposes leading some to think it had been contrived by the Soviet leadership), graduated as a engineer, and became a prominent politician and international representative of the USSR.

To read a biography of Valentina Tereshkova see the Encyclopedia Astronautica site.

Related posts

First man-made object to reach the Moon, 14th September 1959

Launch of Apollo 13, 11th April 1970

Only spaceflight of Buran, 15th November 1988

15 June 2009

On this day in history: Josiah Henson born, 1789

The man who partly inspired Harriet Beecher Stowe's character of Uncle Tom was born into slavery on 15th June 1789 in Charles County, Maryland, on the farm of Francis Newman. Newman owned his father and leased his mother from Dr. Josiah McPherson. As a child Josiah witnessed his father receiving one-hundred lashes followed by the cutting off of his ear. The punishment was meted out because his father attacked a white overseer for assaulting Josiah's mother. Later, Newman sold Josiah's father to a new owner in Alabama, never to be seen by his family again.

The man who partly inspired Harriet Beecher Stowe's character of Uncle Tom was born into slavery on 15th June 1789 in Charles County, Maryland, on the farm of Francis Newman. Newman owned his father and leased his mother from Dr. Josiah McPherson. As a child Josiah witnessed his father receiving one-hundred lashes followed by the cutting off of his ear. The punishment was meted out because his father attacked a white overseer for assaulting Josiah's mother. Later, Newman sold Josiah's father to a new owner in Alabama, never to be seen by his family again.

After the sale, Josiah and his mother returned to the estate of Dr. McPherson who named the young slave after himself. According to Henson, the doctor was a kindly man but a drunkard who was found drowned in a stream that he was apparently too inebriated to cross safely. McPherson's estate was sold off by his heirs, the sale included Josiah's mother and five older siblings. Josiah was initially sold to a tavern keeper called Robb, he was neglected and became sickly. As a result he was sold at a bargain price to his mother's new owner, Isaac Riley, after Josiah's mother begged Riley to let her tend for her youngest child.

Josiah repaid Riley's kindness by working hard on his land, eventually becoming the farm manager. While on the estate of Riley's brother, Amos, in Kentucky, he became a Methodist preacher and raised a family of his own. Nevertheless, he yearned for freedom and in 1829 gave his owner the $350 he had saved from preaching to buy his freedom, only to learn that Amos Riley had increased his price from the agreed $450, with $350 initial cash payment, to one-thousand dollars. His hopes of manumission dashed, he later learnt that he and his family might be sold again so he resolved to escape to freedom.

Henson, his wife and children crossed the Niagara River in October 1830, setting foot in the Province of Upper Canada where they effectively became free. Wishing to help his fellow escaped slaves, Josiah used money he had raised in the four years after arriving in Canada to found a two-hundred acre self-sufficient community in Dawn Township, near Dresden in Kent County. Over five hundred people lived at the Dawn Settlement, which exported black walnut to the United States and Britain.

He travelled to England a number of times to promote the community's wares and also to speak at meetings. In 1851 he travelled across the ocean to show his wares at the Great Exhibition. When Queen Victoria passed his display she asked whether he was indeed a fugitive slave, since his works carried the legend: "This is the product of the industry of a fugitive slave from the United States, whose residence is Dawn, Canada."

Josiah Henson died on 5th May 1885, in Dresden Ontraio, aged 94. Since his death he has received many honours: he was the first black man to appear on a Canadian stamp; his home and other buildings on the site of Dawn Settlement are preserved; and, in 1999 the Historic Sites and Monuments Board of Canada declared him a National Historic Person and installed a plaque outside his relocated and restored cabin.

The University of North Caroline hosts a hypertext version of "Uncle Tom's Story of his life." An Autobiography of the Rev. Josiah Henson (Mrs. Harriet Beecher Stowe's "Uncle Tom"). From 1789 to 1876.

Related posts

Constitution of Vermont abolished slavery, 7th July 1777

Haitian Revolution, 22nd August 1791

All slaves emancipated in British Empire, 1st August 1834

French Abolished Slavery for Second Time, 28th April 1848

14 June 2009

On this day in history: Ottomans conquered the Kingdom of Sennar, 1821

The Kingdom of Sennar was created at the dawn sixteenth-century when the Funj people led by Amara Dunqas conquered much of modern day Sudan. About twenty years later the Amara Dunqas converted from a fusion of Christianity and animism to Islam and took the title Sultan. Later that century Sennar reached its peak, having conquered many of its neighbours and posing a credible threat to Ethiopia to the south and Egypt to the north.

The Kingdom of Sennar was created at the dawn sixteenth-century when the Funj people led by Amara Dunqas conquered much of modern day Sudan. About twenty years later the Amara Dunqas converted from a fusion of Christianity and animism to Islam and took the title Sultan. Later that century Sennar reached its peak, having conquered many of its neighbours and posing a credible threat to Ethiopia to the south and Egypt to the north.

The seventeenth century was a period of slow decline for the Sultanate, as the monarch lost control of the economy, due to an influx of foreign currency, and the law, as Islamic legal scholars asserted their authority. Between 1769 and 1788 the Sultans were merely puppets of the Hamaj who following a successful revolt held the reigns of power as regents. As the sultans struggled to re-establish their rule and the regents fought to maintain their hold over the running of the country, the country became weakened and a target for the imperial ambitions of foreign powers.

In 1821, the army of general Ismail bin Muhammed Ali, son of the khedive of Ottoman Egypt, invaded Sennar. The forces of the Sultan, Badi VII, offered no resistance and on 14th June surrendered to Ismail, offering gifts and then having to watch the Ottoman troops loot his capital. Badi was restored as nominal rule of his lands, which were henceforth part of the Ottoman Empire.

Related posts

Shortest war in history, 27th August 1896

13 June 2009

On this day in history: Queen Victoria`s first train journey, 1842

On Wednesday 13th June 1842, Queen Victoria became the first reigning British monarch to travel by railway. The Great Western Railway (GWR) built her a special royal coach to convey her from the station at Slough in Berkshire to London Paddington station. The idea for the journey had originated with the Queen whose officials contacted the authorities at Paddington the previous Saturday. The staff at the GWR quickly drew up plans for the trip in the utmost secrecy, possibly in response to an attempt on the Queen's life the month before while she travelled in a carriage through St. James' Park, London.

On Wednesday 13th June 1842, Queen Victoria became the first reigning British monarch to travel by railway. The Great Western Railway (GWR) built her a special royal coach to convey her from the station at Slough in Berkshire to London Paddington station. The idea for the journey had originated with the Queen whose officials contacted the authorities at Paddington the previous Saturday. The staff at the GWR quickly drew up plans for the trip in the utmost secrecy, possibly in response to an attempt on the Queen's life the month before while she travelled in a carriage through St. James' Park, London.

The royal party, consisting of Victoria, her husband Prince Albert, and her cousin Count Mensdorf, arrived at Slough station at just before midday and the train, consisting of the Royal saloon and six other coaches, left promptly at 12:00pm. The Firefly class locomotive called Phlegethon, which hauled the train was driven by Daniel Gooch, the GWR's chief mechanical engineer (who designed the Firefly class locomotives), accompanied by Isambard Kingdom Brunel, the chief engineer of the GWR.

After a twenty-five minute journey, the train arrived at the Paddington terminus where the Queen was received by the directors and officers of the railway company and their wives, a detachment of the 8th Royal Irish Hussars, and a crowd of cheering onlookers. Following the reception the royal carriage conveyed the royal party to Buckingham Palace, where she arrived at 1pm.

Queen Victoria continued to use the railways regularly, and even bore some of the cost for one of the royal carriages from her own purse. A particular favourite with the royal family was the annual train journey up to Balmoral in Scotland, which they undertook each autumn. The Queen required that the speed of the train not exceed 40 mph during the day nor 30 mph at night, and would have to halt completely if she chose to eat. In spite of her reticence about some elements of travel by train, Victoria's approval of that system of transport must surely have done much to make it popular not only with the less fortunate, but also with the ruling classes of Britain.

Related posts

The world`s first public railway opens, 27th September 1825

Tom Thumb beat a horse, 28th August 1830

First underground railway opened, 10th January 1863

Steam locomotive world speed record, 3rd July 1938

Last steam-hauled mainline passenger train on British Railways, 11th August 1968

12 June 2009

On this day in history: Philippine Declaration of Independence from Spain, 1898

In March 1521, Ferdinand Magellan became the first European to set foot on one of the islands now known as the Philippines. He named them the Islas de San Lazaro and claimed them for Spain. He set about establishing friendly relationships with the islanders and converting them to Catholicism; however, he became involved in local rivalries between the tribes and took part in the Battle of Mactan during which he was shot with a poisoned arrow and killed.

In March 1521, Ferdinand Magellan became the first European to set foot on one of the islands now known as the Philippines. He named them the Islas de San Lazaro and claimed them for Spain. He set about establishing friendly relationships with the islanders and converting them to Catholicism; however, he became involved in local rivalries between the tribes and took part in the Battle of Mactan during which he was shot with a poisoned arrow and killed.

Following Magellan's death his remaining crew abandoned the islands. The Spanish king, Charles I, sent successive expeditions to the islands. During one of these the islands were renamed as the Las Islas Felipinas in honour of Prince Philip, who was crowned king of Spain in 1556, following the abdication of his father. Early in his reign Philip ordered a fleet to sail for the east. Officially the expedition was one of discovery; in reality it was an expedition of conquest.

Over the next five years the conquistadores defeated the native kingdoms and established colonial rule. The repressive policies of the Spanish resulted in a succession of revolts by native islanders and the Chinese communities on the islands. Nevertheless, the Spanish managed to put down the rebellions and maintain control in the face of many invasions from other colonial powers.

The revolts of the nineteenth century took on a distinctly nationalist character and involved islanders of Spanish descent, called Insulares. These included emergent middle classes, well educated and versed in liberal ideas, called the Ilustrados("erudite" or "learned"). The Ilustrados came into conflict with the Peninsulares, the Spanish-born ruling class, over the issue of secularization of Philippine churches whereby native-born priests would take over church affairs in place of clergy belonging to religious orders.

The 1869 liberal victory in Spain resulted in the assignment of Carlos María de la Torre as Governor-General of the islands. He instituted a series of liberal reforms, but opposition from the Peninsulares friars led to his recall to Spain and his replacement with the more hard-liner, Rafael Izquierdo. When Izquierdo dismantled the reforms and managed to alienate the islands' soldiery by subjecting them to personal taxation. Consequently, some of Fort San Felipe garrison mutinied, hoping to spark a national uprising. Nevertheless, the Cavite Mutiny of 1872 was unsuccessful and Izquierdo took the opportunity to deportation many nationalist leaders.

The repressive measures did not end the nationalist cause. In 1892, radical members of La Liga Filipina ("The Philippine League") founded the revolutionary group known as the Katipunan led by Andrés Bonifacio, Ladislao Diwa, Teodoro Plata, Valentín Díaz, and Deodato Arellano. They elected Andrés Bonifacio as the leader of a rebel army. The Katipunan managed to publish two issues of a newspaper called Libertad ("Freedom") before the colonial authorities suppressed it and arrested a number of their leaders. Threatened with arrest the remaining leaders decided to go on the offensive and in August 1896 the revolution began when they tore up their Cedulas ("tax certificates") shouting "Long live the Philippines!" in an act that became known as "Cry of Pugad Lawin".

In spite of a major defeat at San Juan del Monte in Manila, the revolutionaries inspired revolts in neighbouring provinces. Overcoming factional differences the revolution grew in strength, achieving a series of victories. Nevertheless, the arrival of Spanish reinforcements forced the revolutionaries to sign a peace treaty called the Pact of Biak-na-Bato in 1897, which required the exile of the leading revolutionaries in return for a general amnesty and monetary compensation.

The following year the outbreak of war between the United States and Spain gave the revolutionaries the opportunity they had been waiting for. In May, a U.S. fleet destroyed the Spanish fleet at the Battle of Manila Bay and set up a blockade. On 12th July 1898 the revolutionary forces of General Emilio Aguinaldo made a declaration of independence at his ancestral home at Cavite el Viejo (now called Kawit). Ambrosio Rianzares Bautista read The Act of the Declaration of Independence, which he had written. Ninety-eight people then signed the Declaration, including an American military officer who acted as witness. As part of the ceremony they raised the National Flag of the Philippines, made in Hong Kong by Mrs. Marcela Agoncillo, Lorenza Agoncillo and Delfina Herboza, after which they performed their national anthem, the Marcha Filipina Magdalo.

Philippine independence did not last for long. In December 1898 the Spanish and Americans signed the Treaty of Paris, by which Spain surrendered the Philippines to the United States. Despite the establishment of an elected government by the revolutionaries the American government appointed a military governor to rule the islands resulting in the Philippine–American War of 1899–1913. On 4th July 1946, the Philippines finally achieved full independence following the liberation of the islands from Japanese occupation.

An English translation of The Act of Declaration of Philippine Independence is available to read on filipino.biz.ph.

Related posts

Venezuelan Declaration of Independence, 5th July 1811

Peruvian independence declared, 28th July 1821

Indonesian independence declared, 17th August 1945

Also on this day in history

French Government banned student organisations, 1968

11 June 2009

On this day in history: Lowest innings total in first-class cricket, 1907

On 11th June 1907, Gloucestershire resumed batting on the second day of their English County Cricket Championship match against Northamptonshire at the Spa Ground in Gloucester. At the end of a rain affected day-one the home side had scored a meagre twenty runs for the loss of four wickets. They went on to score a total of sixty runs before they were bowled out. After a short break the teams took to the field for Northamptonshire's first innings. The Times newspaper report of 12th June detailed what happened next:

On 11th June 1907, Gloucestershire resumed batting on the second day of their English County Cricket Championship match against Northamptonshire at the Spa Ground in Gloucester. At the end of a rain affected day-one the home side had scored a meagre twenty runs for the loss of four wickets. They went on to score a total of sixty runs before they were bowled out. After a short break the teams took to the field for Northamptonshire's first innings. The Times newspaper report of 12th June detailed what happened next:

In the course of 40 minutes [...] Northamptonshire were got out by [Edward] Dennett [pictured] and Mr. [Gilbert] Jessop for 12 runs. The ground, of course, greatly favoured the bowlers; but no men could have used the opportunity better than this pair did. While Mr. Jessop kept a perfect length and so kept the runs down, Dennett got rid of his opponents in startling fashion. Before a wicket fell six were scored from him, but afterwards only three more were hit off his bowling, while he claimed eight wickets.

Jessop took the remaining two wickets. Gloucestershire scored 88 in their second innings, and Northamptonshire reached 40 for 7 at the end of the second day's play, with Dennett taking all the wickets with only twelve runs scored off his bowling. The weather prevented any play on day-three so this historical match ended in a draw.

The scorecard for this match is available at CricketArchive.com.

Related posts

Garry Sobers hit six sixes in an over, 31st August 1968

10 June 2009

On this day in history: First execution in Salem witch trials, 1692

Between February 1692 and May 1693, the fear of witchcraft drove the communities of three counties in the colonial state of Massachusetts into a panic that cost the lives of at least twenty-five people.

Between February 1692 and May 1693, the fear of witchcraft drove the communities of three counties in the colonial state of Massachusetts into a panic that cost the lives of at least twenty-five people.

The hysteria began when two young cousins, Betty Parris and Abigail Williams (aged nine and twelve respectively) began to suffer from uncontrollable fits and behave in an unruly manner. Soon other girls in Salem village began behaving in a similar manner. With no obvious explanation for this behaviour, the villagers suspected that it was the work of witches.

Initially, three women had accusations levelled against them. Each woman lived on the margins of the dominant puritan society: Tituba a servant of non-European ethnicity who accused the other two while under interrogation; Sarah Good, who relied on charity to survive; and, Sarah Osborne, who married her indentured servant and rarely attended church.

Over the next few months, a spate of accusations resulted in a series of arrests in Salem and nearby villages. Those arrested included two churchgoing women: moral propriety was no longer a protection against accusation. By the end of May, the magistrates held sixty-two people in custody. Early the next month the Court of Oyer and Terminer convened in Salem to prosecute the cases.

The first case brought before the Chief Magistrate, William Stoughton, was that of the fifty-nine year old Bridget Bishop, who had a reputation for being outspoken and dressing in a flamboyant manner by puritan standards. Her trial took place on 2nd June without a counsel for the defence. She was found guilty the same day and sentenced to execution by hanging.

On the 10th June 1692, Bridget Bishop was hanged - the first of fourteen women and four men to suffer that fate before the hysteria had run its course. In October 1711, the Great and General Court of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts (the grand title of the state legislature) passed an act exonerating twenty-two of the executed, but not Bridget Bishop. 1957 another act exonerated the rest of those executed as a result of the witch trials, but only one - Ann Pudeator - was named. Finally, in 2001 the Court passed an act declaring all the accused to have been innocent.

The University of Virginia hosts the web pages of the Salem Witch Trials Documentary Archive and Transcription Project - an excellent collection of primary source materials.

Related posts

The funeral of Pocahontas, 21st March 1617

Slave rebellion in Richmond, Virginia, 30th August 1800

9 June 2009

On this day in history: Raid on the Medway, 1667

The Restoration of the Stuart monarchy in Britain in 1660 did not mean an end to all of the policies of Oliver Cromwell and the Commonwealth, especially with regard to trade. At that time the United Provinces of the Netherlands dominated world trade, a position that the English regarded with jealous eyes. Trade disputes - mainly caused by restrictions on foreign trade to English ports brought about by the Navigation Act of 1651 - and the English use of privateers to search Dutch merchantmen brought the two countries into open conflict during Cromwell's reign.

The Restoration of the Stuart monarchy in Britain in 1660 did not mean an end to all of the policies of Oliver Cromwell and the Commonwealth, especially with regard to trade. At that time the United Provinces of the Netherlands dominated world trade, a position that the English regarded with jealous eyes. Trade disputes - mainly caused by restrictions on foreign trade to English ports brought about by the Navigation Act of 1651 - and the English use of privateers to search Dutch merchantmen brought the two countries into open conflict during Cromwell's reign.

The First-Anglo Dutch War lasted from March 1652 to May 1654. Fought entirely at sea it resulted in an English victory. As part of the Treaty of Westminster, the Dutch reluctantly recognised the Navigation Act; however, the underlying issues that brought the countries to war had not been resolved. The Dutch response to a series of diplomatic incidents and English attacks on Dutch colonies and shipping provided the pretext for the English to declare war on 4th March 1665.

As with the first war, the fighting was limited to naval engagements; mostly confined to the North Sea. The initial English successes did not provide the decisive victory required to force another capitulation from the Dutch. Indeed, the strength of the reconstructed Dutch navy and their financial might meant that as the war dragged on into 1667, the British king, Charles II, struggled to find the money to maintain his navy. As a result of this, he decided to moor his largest ships at Chatham Docks, on the River Medway, while he negotiated with the Dutch and conducted secret talks with the French for extra funds. Meanwhile, the Dutch made plans to end the war with a decisive blow: an amphibious assault on Chatham Docks.

The plan was hatched by the Dutch statesman, Johan de Witt, whose brother Cornelis accompanied the force with the sealed orders for the attack - secrecy being of the utmost importance. Late in the day on 9th June 1667, the English sighted thirty ships entering the Thames Estuary. The attacking fleet carried around one-thousand marines, who captured strategic positions at Canvey Island and Sheerness on either side of the mouth of the river. Over the next few days the Dutch fought their way up the Thames and then the Medway removing the ships sunk by the English to impede their progress. On 12th June, the Dutch engaged the Royal Navy ships defending the chain at Gillingham, which protected the docks. Once they captured the HMS Unity and destroyed the Matthias and Charles V with a fireships, the docks were at their mercy.

In response, the Royal Navy sank the ships further up the river to prevent their capture - in total they sank thirty of their own ships during the raid. The Dutch seamen continued to fight their way into the docks until their withdrawal on the 14th June. The mission was a complete success, the Dutch destroyed fifteen ships and sailed away with two more, including the pride of the English fleet: HMS Royal Charles. With his Navy in tatters, King Charles II was left with little choice but to sue for peace. A month later his representatives signed the Treaty of Breda, which granted the Dutch possession of some of the territories they captured during the war, concessions regarding the Navigation Act, and also freed up their forces just as the French invaded the Spanish Netherlands to their south.

You can read a contemporary account of the raid in the Diary of Samuel Pepys available at Project Gutenberg.

Related posts

Battle of St George`s Caye, 10th September 1798

British capture of Hong Kong, 23rd August 1839

Shortest war in history, 27th August 1896

8 June 2009

On this day in history: Catastrophic volcanic eruption in Iceland, 1783

During the mid-morning of 8th June 1783, a Lutheran priest in southern Iceland called Jon Steingrimsson witnessed the first results of one of the most catastrophic volcanic eruptions in history:

During the mid-morning of 8th June 1783, a Lutheran priest in southern Iceland called Jon Steingrimsson witnessed the first results of one of the most catastrophic volcanic eruptions in history:

[In] clear and calm weather, a black haze of sand appeared to the north of the mountains. The cloud was so extensive that in a short time it had spread over the entire area and so thick that it caused darkness indoors. That night, strong earthquakes and tremors occurred. [1]

The earth had ripped apart along a sixteen-mile fissure later called the Laki volcano. This fissure intermittently continued to spew lava over the next eight months until its last eruption on 7th February 1784. The results of this eruption were felt across Europe, parts of North America and reportedly as far afield as Asia and North Africa. Understandably, the effects were worst in Iceland where an estimated quarter of the population died as a result.

Diaries and letters of the time help the historian trace the impact of the volcano. In Norway, on the 10th June, Johan Brun (also a Lutheran priest) wrote in his diary about black ash that had fallen from the sky causing plants to whither. Over the next week the dust cloud reached Prague and Berlin. An apparent change in direction of the prevailing winds, meant the 'dry fog' then passed over France on the 18th before it arrived over Britain on the 22nd.

Wherever the cloud appeared, those people who worked the land became ill. As the English poet William Cowper wrote in a letter to Rev. William Unwin in September 1783:

[S]uch multitudes are indisposed by fevers in this country, that the farmers have with difficulty gathered in their harvest, the labourers having been almost every day carried out of the field incapable of work; and many die. [2]

The climactic impact of the eruptions were felt for many years, and may have contributed to the poor harvests across Europe in 1788, which are often seen as a key cause of the French Revolution.

To learn more about the Laki eruptions and their environmental impact, see this excellent article on The Economist web-site.

[2] W. Cowper, The works of William Cowper Vol. III (London, 1854) - available at Google Books

Related posts

Last recorded eruption of Mount Fuji, 16th December 1707

Mino-Owari earthquake, 28th October 1891

7 June 2009

On this day in history: Dissolution of Union between Sweden and Norway, 1905

At the beginning of the nineteenth century Denmark joined the Second League of Armed Neutrality, which had the aim of protecting neutral shipping from the British policy of searching all ships for French contraband. In response the British decided that Denmark had become and aggressor, driving the Danes closer to Napoleon Bonaparte's France. Following the defeat of Napoleon, the victorious Sweden signed the Treaty of Kiel (1814) with the defeated King of Denmark, who ceded Norway to the Swedes in return for lands in Pomerania.

At the beginning of the nineteenth century Denmark joined the Second League of Armed Neutrality, which had the aim of protecting neutral shipping from the British policy of searching all ships for French contraband. In response the British decided that Denmark had become and aggressor, driving the Danes closer to Napoleon Bonaparte's France. Following the defeat of Napoleon, the victorious Sweden signed the Treaty of Kiel (1814) with the defeated King of Denmark, who ceded Norway to the Swedes in return for lands in Pomerania.

The Norwegians ignored the treaty and declared independence. In response, the Swedish king, Karl XIII launched a military campaign in the summer of 1814. The short war ended with the Convention of Moss, a ceasefire and negotiated settlement by which the Norwegian government accepted a loose personal union with Sweden. Norway became a relatively autonomous constitutional monarchy with Karl as king.

By the end of the nineteenth century the union began to show signs of strains. The protectionist measures adopted by the Swedish government affected the Norwegian economy, which was more dependent on foreign trade. Tensions escalated when a succession of Norwegian governments demanded that they be allowed to send their own consuls aboard rather than rely on those appointed by the Swedish foreign minister.

King Oscar II dismissed the Norwegian demands, declaring that such a measure would erode his right to decide on foreign policy. As a consequence of royal intransigence the Norwegian Conservative politicians joined their Liberal counterparts who had long insisted on greater autonomy for their country. In 1905 the Liberal politician and shipping magnate formed a coalition government with the Conservatives. The government had one goal, to enact legislation in the Norwegian parliament (called the Storting) to allow them to appoint their own consuls.

When the king vetoed the legislation the entire government resigned in protest. Oscar declared that he was unable to form a government under those circumstances and in response on 7th June 1905, the Storting unanimously declared that the union with Sweden to be effectively dissolved. In an address they stated,

Whereas all the members of the Cabinet have to-day, in the Storthing, resigned their posts, and whereas Your Majesty in the Protocol of May 27 officially declared that Your Majesty did not see your way clear to create a new Government for the country, the Constitutional Regal power in Norway has thereby become inoperative.

It has therefore been the duty of the Storthing, as the representative of the Norwegian people, without delay to empower the members of the resigning Cabinet to exercise until further notice as the Norwegian Government the power appertaining to the King in accordance with the Constitution of the Kingdom of Norway and the existing laws with the changes which are necessitated by the fact that the union with Sweden, which provides that there shall be a common King, is dissolved in consequence of the fact that the King has ceased to act as King of Norway.

Initially, the Swedish government decried the declaration as an act of rebellion; however, they were open to a negotiated settlement but they demanded that the Norwegian people be asked to decide the future of their state.

The Storting passes the resolution to disolve the union.