In 1968, Richard Hooker (r.n. H. Richard Hornberger) published a novel called MASH: A Novel About Three Army Doctors. He based the book, which he wrote in collaboration with the sports writer W.C. Heinz, on his experiences as a surgeon at the 8055th Mobile Army Surgical Hospital during the Korean War, basing the character of Hawkeye Pierce on himself. Two years later 20th Century Fox released a movie adaptation of the book directed Robert Altman and starring Elliot Gould as "Trapper John" and Donald Sutherland as "Hawkeye".

In 1968, Richard Hooker (r.n. H. Richard Hornberger) published a novel called MASH: A Novel About Three Army Doctors. He based the book, which he wrote in collaboration with the sports writer W.C. Heinz, on his experiences as a surgeon at the 8055th Mobile Army Surgical Hospital during the Korean War, basing the character of Hawkeye Pierce on himself. Two years later 20th Century Fox released a movie adaptation of the book directed Robert Altman and starring Elliot Gould as "Trapper John" and Donald Sutherland as "Hawkeye".

The success of the feature film prompted 20th Century Fox to produce a television series. The first episode of M*A*S*H appeared on the CBS network on 17th September 1972. The ensemble cast included only one of the actors from the movie version, Gary Burghoff as "Radar." Alan Alda took the role of "Hawkeye"; Wayne Rogers appeared as "Trapper" (for the first three seasons); Loretta Swit played "Hot Lips" Houlihan; Larry Linville portrayed "Frank" Burns, who was often the butt of the other surgeons joke.

While not an instant hit, the show's popularity grew over time and eleven series were produced. On 28th February 1983, the 251st and final episode of M*A*S*H aired, telling the story of the end of the Korean War and the effect this had on the show's characters. Nearly 106 million Americans watched the two-and-a-half hour special entitled "Goodbye, Farewell and Amen", which remains the most viewed episode of the television series in the United States to this day.

Related posts

BBC Television Service started broadcasting: 2nd November 1936

First national telecast of the Kentucky Derby: 3rd May 1952

First broadcast of Doctor Who: 23rd November 1963

Customised search for historical information

28 February 2011

On this day in history: Last episode of M*A*S*H broadcast, 1983

26 February 2011

On this day in history: Napoleon escaped from Elba, 1815

On 15th August 1769, Napoleon Bonaparte was born in the town of Ajaccio, on Corsica, a year after the island became a French territory. The wealth and political influence of his family enabled him to be schooled in mainland France. Initially he attended a religious school in Autun, then the military academy at Brienne-le-Château and finally the prestigious École Militaire in Paris where he trained to be a artillery officer.

On 15th August 1769, Napoleon Bonaparte was born in the town of Ajaccio, on Corsica, a year after the island became a French territory. The wealth and political influence of his family enabled him to be schooled in mainland France. Initially he attended a religious school in Autun, then the military academy at Brienne-le-Château and finally the prestigious École Militaire in Paris where he trained to be a artillery officer.

In September 1785, Bonaparte became a second lieutenant in La Fère artillery regiment. During the early stages of the French Revolution, he returned to Corsica on an extended leave of absence, where he commanded a volunteer battalion in support of the radical revolutionaries. In 1793 Bonaparte published a pamphlet in favour of the republican cause which secured for him the support of Augustin Robespierre, the younger brother of the Revolutionary leader.

This patronage resulted in him being given the command of the artillery during the siege of Toulon, which British troops occupied. In recognition of Bonaparte's role in the successful assault on the city, the Republican authorities promoted him to Brigadier-General and gave him command of the artillery in the French army on the Italian border. Nevertheless, he spent a short time in prison in August 1794 following the fall of Robespierre due to his relationship with his brother.

After being released, Napoleon returned to military service but remained out of favour, losing his position as a general. Fortune smiled on Bonaparte again in 1795 when he took command of the forces defending the Republican government during a royalist uprising. In gratitude the new government, called the Directory, promoted him to Commander of the Interior and gave him command of the Army of Italy.

Successful campaigning in Italy brought Napoleon both fame and political influence. He then undertook a colonial expedition to seize Egypt and disrupt British access to India. The campaign proved to be a failure and Napoleon left an army ravaged by disease to return to France, where in 1799 he took part in a coup and became one of a number of provisional Consuls that ruled France.

Napoleon outmanoeuvred his fellow consuls and secured his election as First Consul for Life, effective becoming dictator. During a period of peace following the Treaty of Amiens, Bonaparte set about reforming the administration of France and repairing the infrastructure. During this period both Jacobins and Royalists plotted his overthrow, which gave him the excuse to revive the hereditary monarchy with himself as Emperor of the French. Bonaparte also placed his family and friends on the thrones of European states conquered by the French during the Revolutionary Words, including having himself crowned as King of Italy.

In 1805 the British persuaded the Austrians and Russia to join a coalition against the French. Napoleon gathered an army at Boulogne to invade Britain, but after failing to achieve naval dominance in the Channel he sent this Grande Armée to march into Germany. While the British dominated the seas, Bonaparte's army enjoyed a string of successes across Europe forcing the Austrians to sign a peace treaty. The British then formed a new coalition including Prussia but the dominance of Bonaparte's armies again resulted in the defeat of the continental powers, which he forced to join his Continental System to boycott British goods in a form of economic warfare. When Portuguese would not join the boycott Napoleon sent an army to invade Portugal with the support of the Spanish in 1807.

The Peninsular War marked the turning point in his fortunes as the English and Portuguese armies commanded by Arthur Wellesley, later the Duke of Wellington, drove the French back. In 1809, Austria broke its alliance with France opening a second front and further weakening the French. When the Russians failed to comply with the Continental System, Napoleon led the Grande Armée to invade Russia.

The disastrous campaign and humiliating retreat undermined Napoleon's rule. Following a series of further defeats and the capture of Paris by the Coalition, the Marshals of the French army confronted Bonaparte and forced him to abdicate. While peace negotiations took place between the French and the Coalition countries, Napoleon travelled into exile on the Mediterranean island of Elba. Napoleon retained the title of Emperor but his empire only comprised the island and its twelve-thousand inhabitants. After a failed suicide attempt Napoleon took charge of Elba creating a small military force and modernising the island.

After hearing that the Coalition were about to send him into exile on a remote Atlantic island, on 26th February 1815 Napoleon escaped captivity on Elba with around six-hundred men, arriving in France two days later. The 5th Infantry Regiment intercepted him at Grenoble, but rather than taking him into custody they acclaimed his as their Emperor. The return of Napoleon was similarly welcomed across much of France and he soon wrested the reigns of power away from the restored Bourbon monarchy.

With the loyalty of the senior army officers re-established, Napoleon marched in triumph into Paris on 19th March. After another series of constitutional reforms and mobilisation of the armed forces, he again took France to war against a new Coalition in a pre-emptive strike. His defeat at the Battle of Waterloo and his consequent surrender finally ended his reign. This time he was exiled on a remote island in the South Atlantic called Saint Helena, where he died in May 1821.

Related posts

Cisalpine Republic created: 29th June 1797

French Protestants granted freedom of worship: 8th April 1802

Louisiana Purchase Treaty signed: 30th April 1803

Prince Murat executed: 13th October 1815

24 February 2011

On this day in history: Shri Swaminarayan Mandir inaugurated, 1822

Ghanshyam Pande was born in the village of Chhapaiya, Uttar Pradesh, Northern India in 1781. At the age of eleven he left on a seven year pilgrimage across India after which he settled in the state of Gujarat in Western India. While there he became an initiate of the Uddhav Sampraday Hindu sect, under the name Sahajanand Swami. Three years later his guru, Ramanand Swami, handed over control of the Uddhav Sampraday to Sahajanand before he died.

Ghanshyam Pande was born in the village of Chhapaiya, Uttar Pradesh, Northern India in 1781. At the age of eleven he left on a seven year pilgrimage across India after which he settled in the state of Gujarat in Western India. While there he became an initiate of the Uddhav Sampraday Hindu sect, under the name Sahajanand Swami. Three years later his guru, Ramanand Swami, handed over control of the Uddhav Sampraday to Sahajanand before he died.

Two weeks after the death of his guru, Sahajanand Swami held a gathering of the sect in Faneni. He asked those gathered to repeatedly chant the word Swaminarayan. During the chanting of this mantra a number of the gathering entered a trance state realising that Sahajanand Swami to be a divine incarnation. Henceforth Sahajanand Swami became known as Swaminarayan and the Uddhav Sampraday became the Swaminarayan Sampraday.

On 23rd February 1822, Swaminarayan inaugurated the first temple of Swaminarayan Sampraday, the Shri Swaminarayan Mandir in Ahmedabad, Gujarat, when he installed the murtis (icons) of various deities including himself. The chief architect, Ananandand Swami, built the shrine with intricate Burma teak carvings in keeping with the scriptural requirements on land gifted to Swaminarayan by the British Imperial Government. Apart from himself, Swaminarayan installed murti forms of a number of other Hindu deities including NarNarayan Dev in the principle position of worship in the temple, Radhakrishna Dev, Dharmadev, BhaktiMata and Harikrishna.

Swaminarayan ordered the construction of a further eight temples of which five were completed during his lifetime. Before his death he established a dual Acharyaship to lead the sect following his death. In a legal document (known as Desh Vibhag no Lekh) he named his two successors as Ayodhyaprasadji Maharaj and Raghuveerji Maharaj. Swaminarayan departed from his mortal body on 1st June 1830 at the age of 49.

Related posts

Mumtaz Muhal died: 17th June 1631

Oldest surviving synagogue in North America dedicated: 2nd December 1763

Cologne Cathedral completed: 14th August 1880

23 February 2011

On this day in history: Juan Fangio kidnapped in Cuba, 1958

On 23rd February 1958, the Argentinian racing car driver Juan Fangio, was approached by a man brandishing a revolver in the lobby of the Hotel Lincoln in Havana, Cuba. The man was Manuel Uziel, a member of Fidel Castro's 26th of July Movement then struggling to overthrow the regime of President Batista. Uziel asked Fangio to identify himself, but the five time Formula One Champion thought it was some sort of joke, until Uziel was joined by several other rebels carrying sub-machine guns. They explained that they intended to keep him captive until after the Cuban Grand Prix, in which Fangio was going to defend his title the following day.

On 23rd February 1958, the Argentinian racing car driver Juan Fangio, was approached by a man brandishing a revolver in the lobby of the Hotel Lincoln in Havana, Cuba. The man was Manuel Uziel, a member of Fidel Castro's 26th of July Movement then struggling to overthrow the regime of President Batista. Uziel asked Fangio to identify himself, but the five time Formula One Champion thought it was some sort of joke, until Uziel was joined by several other rebels carrying sub-machine guns. They explained that they intended to keep him captive until after the Cuban Grand Prix, in which Fangio was going to defend his title the following day.

They took him to an apartment where he received a visit from Faustino Pérez, one of the leaders of the 26th of July Movement, who apologised for the inconvenience. The rebels treated Fangio well, feeding him and giving him a radio so that he could listen to the race, but he chose not to. The race itself ended in disaster after only six laps when the Cuban driver, Armando Garcia, ran into the crowd killing several people and injuring many more.

Good to their word, the rebels released Fangio the following day. He told police that he had been "treated very well - as though I was a friend of the rebels." When asked about the kidnapping he said, "If what the rebels did was in a good cause, then I, as an Argentine, accept it" He declined to identify his captors, with whom he remained good friends.

Related posts

First Formula One Championship race: 13th May 1950

Bay of Pigs: 17th April 1961

22 February 2011

The Year of Revolution: 1848

In a break from the 'On this day in history' series, I am taking inspiration from recent events in Tunisia, Egypt, Bahrain and Libya. This year has seen a wave of revolutions in North Africa and Arabia, but it was Europe that rocked with demands for freedom in 1848. While many of these revolutions failed in the short term, they marked a sea change in European politics.

In a break from the 'On this day in history' series, I am taking inspiration from recent events in Tunisia, Egypt, Bahrain and Libya. This year has seen a wave of revolutions in North Africa and Arabia, but it was Europe that rocked with demands for freedom in 1848. While many of these revolutions failed in the short term, they marked a sea change in European politics.

The year 1848 began with the Sicilian Revolution of Independence, which began on 12th January. This was the third popular rebellion against King Ferdinand II seeking the restoration of the liberal constitution of 1812. Negotiations between the monarch and revolutionaries dragged on for eighteen months before the king's forces finally recaptured the island.

The people of other Italian states also rose up against their rulers, notably in the Kingdom of Lombardy–Venetia, then part of the Hapsburg Austrian Empire. The people of Milan and Venice instituted provisional governments, both of which were eventually defeated by the Austrians. These risings, along with the timely constitutional reforms in the Kingdom of Piedmont-Sardinia, laid the foundations for Italian unification.

Nationalist uprisings occurred elsewhere in the Hapsburg Empire. In March, Magyar nationalists forced Emperor Ferdinand to grant them a constitution and a government. This government ensured Magyar domination of Hungary, resulting in a further uprising of Slovaks in Upper Hungary starting in September, 1848.

The March Revolution in Germany resulted in the short-lived Frankfurt Parliament. This experiment in German unification failed because of the absence of national institutions and the lack support from the King Frederick William IV of Prussia. The final straw was when he turned down the offer of becoming Emperor of the Germans.

The Prussian king faced an uprising in his Polish possessions. In March, a Polish National Committee formed in the Grand Duchy of Poznań, taking inspiration from events in Germany. While the committee negotiated reforms with the Prussians and other Germans, the leader of the Polish militia ignored orders to disarm. This decision resulted in military confrontation with the Prussians whose victory ended any hope of Polish autonomy.

In modern day Romania, Imperial Russian faced liberal nationalist uprisings in Wallachia and Moldavia. Russian troops quickly put down the Moldavian revolt, before turning their attentions to neighbouring Wallachia. With help from the Ottoman Empire the Russians restored their joint hegemony over Danubian Principalities.

1848 saw another revolution in France, the third in less than sixty years. A financial crisis and King Louis Philippe's increasingly conservative policies resulted in a popular uprising in February. The king abdicated and fled to Britain, leaving the way clear for the establishment of the Second Republic.

Further uprisings happened in Belgium, Denmark, Ireland and Schleswig. As with those already detailed, these revolts made little difference in the immediate aftermath, but all these revolutions set the scene for political change in the rest of the nineteenth- and the early twentieth-century. It remains to be seen whether the revolutions in North Africa and Arabia will follow this model of eventual reform, or whether they will quickly establish new governments that endure.

21 February 2011

On this day in history: Nuclear Disarmament logo designed, 1958

Britain started developing nuclear weapons in 1952, but by the end of the decade various groups formed to protest in favour of nuclear disarmament. One such group, the Direct Action Committee Against Nuclear War (DAC), decided to march from Trafalgar Square in London to the Atomic Weapons Research Establishment near Aldermaston in Berkshire over the Easter weekend (4th - 7th April 1958). The Nuclear Disarmament logo made its public début on the march having been adopted by DAC earlier that year at a meeting at the offices of Peace News.

Britain started developing nuclear weapons in 1952, but by the end of the decade various groups formed to protest in favour of nuclear disarmament. One such group, the Direct Action Committee Against Nuclear War (DAC), decided to march from Trafalgar Square in London to the Atomic Weapons Research Establishment near Aldermaston in Berkshire over the Easter weekend (4th - 7th April 1958). The Nuclear Disarmament logo made its public début on the march having been adopted by DAC earlier that year at a meeting at the offices of Peace News.

The design of the logo dates from 21st February 1958, when professional designer and conscientious objector, Gerald Holtom first created it. Holtom later explained the very personal genesis of the design:

I was in despair. Deep despair. I drew myself: the representative of an individual in despair, with hands palm outstretched outwards and downwards in the manner of Goya's peasant before the firing squad. I formalised the drawing into a line and put a circle round it.

The symbol also combines the semaphore letters 'N' (both arms to the side at 45 degree downward angle) and 'D' (one arm held vertically up, the other vertically down), forming the initials of Nuclear Disarmament.

The various nuclear disarmament coalesced into the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament, (CND) founded in 1957. CND adopted Holtom's symbol as well as the Aldermaston march, which it organised yearly. Many anti-nuclear groups and peace activists around the world have adopted the logo, which has become known widely as the peace symbol.

Related posts

Rosenbergs executed: 19th June 1953

First French nuclear test: 13th February 1960

Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty signed: 1st July 1968

Stanislav Petrov averted a nuclear war: 26th September 1983

19 February 2011

On this day in history: Edison patented the phonograph, 1878

In March 1857, the French printer and bookseller, Édouard-Léon Scott de Martinville, patented the first device for recording sound, the phonautograph. His invention inscribed an image on a cylinder coated in lampblack, which he then pressed onto paper. Unfortunately he had no means to play back the sounds that he had recorded. Twenty years later, another Frenchman, the scientist Charles Cros, had the idea of recording sounds by using an oscillating diaphragm to engrave a cylinder that could then be used to produce a similar oscillation. He submitted his idea to the Academy of Science in Paris in a letter that he sealed in an envelope in April 1877, but he did not make any prototypes of his Paleophone, as he called it.

In March 1857, the French printer and bookseller, Édouard-Léon Scott de Martinville, patented the first device for recording sound, the phonautograph. His invention inscribed an image on a cylinder coated in lampblack, which he then pressed onto paper. Unfortunately he had no means to play back the sounds that he had recorded. Twenty years later, another Frenchman, the scientist Charles Cros, had the idea of recording sounds by using an oscillating diaphragm to engrave a cylinder that could then be used to produce a similar oscillation. He submitted his idea to the Academy of Science in Paris in a letter that he sealed in an envelope in April 1877, but he did not make any prototypes of his Paleophone, as he called it.

The following month the American inventor began work on a way to transmit an automated human voice over the telephone. Apparently, quite independently of Cros, he developed a system where the oscillation of a diaphragm was recorded on a cylinder of tinfoil by means of an attached stylus. In November 1877 Edison announced and then demonstrated his phonograph. He submitted the patent application on Christmas Eve that year and on 19th February 1878 Edison received U.S. Patent 0,200,521 (his 117th US patent) for his 'Phonograph or Speaking Machine.'

Related posts

First machine-gun patented: 15th May 1718

Mechanical reaper patented: 21st June 1834

Blue jeans patented: 20th May 1873

First gasoline-driven automobile patented: 29th January 1886

Vacuum cleaner patented: 30th September 1901

First science fiction film released: 1st September 1902

18 February 2011

On this day in history: Pluto discovered, 1930

In 1894 the American businessman Percival Lowell founded an observatory in Flagstaff, Arizona, where he dedicated himself to astronomical research. His theories about canals on Mars resulted in the scientific community ostracising him and his observatory. He also theorised that the orbits of Uranus and Neptune showed the gravitational effects of an unknown Planet X, which he searched for without success from 1905 until his death in 1916. In 1919 William Henry Pickering, the Harvard astronomer and associate of Lowell, predicted the position of Planet X but a study of photographs taken at the Mount Wilson Observatory failed to locate the planet.

In 1894 the American businessman Percival Lowell founded an observatory in Flagstaff, Arizona, where he dedicated himself to astronomical research. His theories about canals on Mars resulted in the scientific community ostracising him and his observatory. He also theorised that the orbits of Uranus and Neptune showed the gravitational effects of an unknown Planet X, which he searched for without success from 1905 until his death in 1916. In 1919 William Henry Pickering, the Harvard astronomer and associate of Lowell, predicted the position of Planet X but a study of photographs taken at the Mount Wilson Observatory failed to locate the planet.

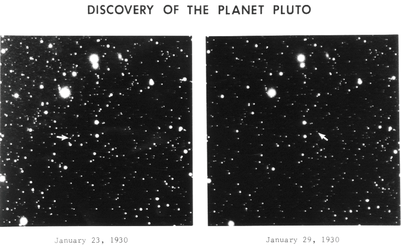

The search for Planet X continued at the Lowell Observatory. In 1929 a young astronomer called Clyde Tombaugh [pictured] started work there after having impressed them with drawings of his observations of Jupiter and Mars. He undertook a systematic review of photographs taken using a 13-inch astrograph. He used blink comparator to flick between photographs taken at different times in order to spot any moving objects. On 18th February 1930 Tombaugh noticed the sort of moving object that he was looking for when he compared two pictures taken on the 23rd and 29th of January. Subsequent observations confirmed that he had found a large stellar body orbiting the Sun.

An Englishman called Falconer Madan, whose brother had suggested the names Deimos and Phobos for the moons of Mars while Science Master at Eton College, read about the discovery of Planet X in The Times. He mentioned the discovery to his granddaughter, Venetia Burney, who suggested that it be named Pluto after the Roman God of the Underworld. He forwarded her suggestion to the British astronomer Herbert Hall Turner who in turn passed it on to the Lowell Observatory. Tombaugh chose Venetia's suggestion over the many others, in part because it began with the letters P and L, the initials of Percival Lovell (and, indeed, of Pickering-Lovell). The name of the new planet became official on 1st May 1930.

Related posts

Foundation stone of Royal Greenwich Observatory laid: 10th August 1675

Neptune discovered: 23rd September 1846

17 February 2011

On this day in history: Volume One of Gibbon`s Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire published, 1776

Edward Gibbon was born in Putney, Surrey, in April 1737 into a wealthy family with Jacobite sympathies. Edward's mother died when he was ten and his father descended into depression, but even before then his parents had been neglectful of their son. Consequently his "Aunt Kitty," Catherine Porten, raised him through his many childhood illnesses.

Edward Gibbon was born in Putney, Surrey, in April 1737 into a wealthy family with Jacobite sympathies. Edward's mother died when he was ten and his father descended into depression, but even before then his parents had been neglectful of their son. Consequently his "Aunt Kitty," Catherine Porten, raised him through his many childhood illnesses.

Despite his continued illness hampering his education, his father secured him a place at Magdalen College, Oxford. His time there was not happy, so rather than attend college he continued his own undirected reading. His voracious appetite for books resulted in him developing an attraction to Catholicism, which he converted to in 1753.

For many Britons of the time, Roman Catholicism was tantamount to treason, particularly for those linked with the Jacobite cause. Within weeks of Edward's conversion, his father sent him to Lausanne, Switzerland, under the care and tutelage of a Reformed pastor called David Pavillard. On Christmas Day, 1754, Edward Gibbon took communion and returned to Protestantism.

Following Gibbon's return to England, in 1759 he enlisted in the South Hampshire militia and was on active duty until December 1762. Meanwhile, he published his first book, Essai sur l'Étude de la Littérature (1761). Following his deactivation from the militia, he traveled around continental Europe on the Grand Tour, including a visit to Rome.

While he was in Rome, Gibbon first conceived of the idea of writing a history of the decline and fall of the ancient city, an idea that he later expanded to take in the entire Roman Empire. Independently wealthy after receiving an inheritance when his father died in 1770, he divided his time between writing and the social whirl of London's literary circle. In 1774 he became a Freemason and also Member of Parliament for Liskeard in Cornwall.

On 17th February 1776, he published the first volume of The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire. The book became an overnight success, earning its author around £1000 and widespread fame. Over the next twelve years he wrote and published a further five volumes. The last three volumes he wrote while living in Lausanne following his retirement from public life.

Gibbon argued that the Roman Empire fell due to the degeneration of civic virtue. He attributed this decline partly to the adoption of Christianity by the Romans who then became more concerned with the prospect of a better life after death and less inclined to make sacrifices for the Empire. An end to the Roman martial spirit and the hiring of barbarian mercenaries to defend the Empire spelled doom.

With his magnum opus completed Gibbon began work on his memoires as well as other historical texts. In 1793, with the French Revolutionary Wars raging across Europe, Gibbon made the perilous journey back to England to comfort a bereaved friend. Gibbon's own health was failing and he died while in London in January 1794 after succumbing to an infection contracted during surgery on a swelling in his groin.

Project Gutenberg hosts all six volumes of Gibbon's Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire.

Related posts

Samuel Johnson`s Dictionary published: 15th April 1755

First edition of Encyclopædia Britannica published: 6th December 1768

First appearance of Sweeney Todd: 21st November 1846

Publication of The Charge of the Light Brigade by Tennyson: 9th December 1854

15 February 2011

On this day in history: Shortest test match in history, 1932

The shortest test in cricketing history in terms of minutes played and balls bowled took place at the Melbourne Cricket Ground during the 1932 South African tour of Australia. The South African captain, 'Jock' Cameron, won the toss and elected to bat as the clouds gathered. The South Africans only managed to score 36 before being bowled out just after the lunch break with Bert Ironmonger, who had been dropped for the previous test, taking five wickets for only six runs.

The shortest test in cricketing history in terms of minutes played and balls bowled took place at the Melbourne Cricket Ground during the 1932 South African tour of Australia. The South African captain, 'Jock' Cameron, won the toss and elected to bat as the clouds gathered. The South Africans only managed to score 36 before being bowled out just after the lunch break with Bert Ironmonger, who had been dropped for the previous test, taking five wickets for only six runs.

The Australian team [pictured] went out to bat without the great Donald Bradman who had badly twisted his ankle in the dressing room before the start of the match. Nevertheless, they managed to score 153 runs on a particularly sticky wicket. Alan Kippax was the top scorer, accumulating 42 runs before being caught by Syd Curnow. The first day's play ended with the South Africans on five runs for the cost of one wicket.

Rain prevented any play on the second day and continued during the rest day. Play finally resumed on the 15th February at 2:15. The South Africans continued to struggle with the wet pitch, being bowled out for only 45 runs with Ironmonger adding another seven wickets to his first innings haul. Australia won the match by an innings and 72 runs after only five and a half hours play in which only 656 balls were bowled.

The match scorecard is available at CricketArchive.

Related posts

Lowest innings total in first-class cricket: 11th June 1907

Garry Sobers hit six sixes in an over: 31st August 1968

13 February 2011

On this day in history: First French nuclear explosive test, 1960

The French have a long association with nuclear research since the days of Marie Curie. In 1945 the French government created the Commissariat à l’énergie atomique (CEA) - the French Atomic Energy Commission - under the direction of the Nobel laureate Jean Frédéric Joliot-Curie. Nevertheless, Joliot-Curie's communist sympathies resulted in him being removed from his position before the beginning of the nuclear power programme in the 1950s.

The French have a long association with nuclear research since the days of Marie Curie. In 1945 the French government created the Commissariat à l’énergie atomique (CEA) - the French Atomic Energy Commission - under the direction of the Nobel laureate Jean Frédéric Joliot-Curie. Nevertheless, Joliot-Curie's communist sympathies resulted in him being removed from his position before the beginning of the nuclear power programme in the 1950s.

In 1956 a secret committee met to review the possible military applications for atomic energy. Work began on delivery systems for nuclear weapons, but another year passed before President René Coty authorised the creation of the Centre Saharien d'Expérimentations Militaires (C.S.E.M.) - a military research facility in what was then the French Sahara. In 1958 the newly installed President Charles de Gaulle gave the final authorisation for France to develop a nuclear bomb, only the fourth country to do so after the United States, the Soviet Union and the United Kingdom.

At 7.04am on 12th February 1960 the scientists at C.S.E.M. conducted their first nuclear explosive test, codenamed Gerboise Bleue ("blue jerboa" - a jerboa is desert rodent). The scientists had mounted the pure fission plutonium implosion device on a 105 meter high tower near Reganne in the desert of Tanezrouf (now in Algeria). The resultant explosion was the most powerful first nuclear test by any nation with a yield of seventy kilotons. They conducted two other tests of much smaller devices in April and December of that year codenamed Gerboise Blanche and Gerboise Rouge - making up the three colours of the tricolore. In April 1961 the scientists detonated the final bomb in the programme, Gerboise Verte.

Footage of the Gerboise Bleue fireball.

Related posts

Rosenbergs executed: 19th June 1953

Nuclear Disarmament logo designed: 21st February 1958

Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty signed: 1st July 1968

Stanislav Petrov averted a nuclear war: 26th September 1983

12 February 2011

On this day in history: Ecuador annexed the Galápagos Islands, 1832

The first European to set foot on the Galápagos Islands was the fourth Bishop of Panama, the Dominican Fray Tomás de Berlanga. In order to settle a territorial dispute between the conquistadors Francisco Pizarro and Diego de Almagro, Berlanga sailed to Peru but strong winds blew his ship off course. He arrived at the islands on 10th March 10 1535 before continuing his journey.

The first European to set foot on the Galápagos Islands was the fourth Bishop of Panama, the Dominican Fray Tomás de Berlanga. In order to settle a territorial dispute between the conquistadors Francisco Pizarro and Diego de Almagro, Berlanga sailed to Peru but strong winds blew his ship off course. He arrived at the islands on 10th March 10 1535 before continuing his journey.

For over two centuries from Richard Hawkin's visit to the islands in 1593, the English pirates and privateers that preyed on Spanish bullion ships and settlements often used the archipelago to evade attack. One such privateer, Woodes Rogers, stopped at the islands to make repairs after having rescued the castaway Alexander Selkirk, who inspired Daniel Defoe's character Robinson Crusoe. The islands attracted a wide range of naturalists including the Italian nobleman Alessandro Malaspina, James Colnett and famously Charles Darwin.

On 12th February 1832, the newly independent Ecuador annexed the islands calling them the Archipelago of Ecuador. The islands initially served as a penal colony governed by General José de Villamil, who sent an exploratory commission there in the previous October. He then set up the Colonising society of the Archipelago of the Galápagos to exploit the lichens that grew there, which served as a dye. Artisans and farmers soon joined the convicts to colonise the islands.

Related posts

Venezuelan Declaration of Independence: 5th July 1811

HMS Beagle launched: 11th May 1820

11 February 2011

On this day in history: Nelson Mandela released, 1990

Nelson Mandela was born on 18th July 1918 in a small village called Mvezo, near Umtata the capital of the Transkei. His father, Gadla Henry Mphakanyiswa, was a member of the Thembu royal family and chief of Mvezo until the colonial authorities removed him following an argument with a European. The family moved to Qunu where Mphakanyiswa died when Nelson was only nine years old.

Nelson Mandela was born on 18th July 1918 in a small village called Mvezo, near Umtata the capital of the Transkei. His father, Gadla Henry Mphakanyiswa, was a member of the Thembu royal family and chief of Mvezo until the colonial authorities removed him following an argument with a European. The family moved to Qunu where Mphakanyiswa died when Nelson was only nine years old.

The regent of the Thembu, Jongintaba, became Mandela's guardian, sending him to a Wesleyan mission school where he was a gifted pupil. Mandela attended a Wesleyan college in Fort Beaufort before enrolling at Fort Hare University, where he became involved in student politics. His involvement in agitation against university policy resulted in him being expelled.

To escape from an arranged marriage, Mandela moved to Johannesburg with Jongintaba, the regent's son. He eventually found employment with a legal firm and completed a BA by correspondence with the University of South Africa. He then began to law at the University of Witwatersand where he first met many people who would later be part of the anti-apartheid movement.

Following the 1948 election victory of the National Party cemented the apartheid policy, Mandela became a political activist. In December 1956 the South African authorities arrested Mandela along with 150 others on charges of treason. A five year trial followed, during which all defendants received acquittals.

To begin with Mandela was committed to the principles of non-violent resistance made famous by Mahatma Gandhi, but in response to an increase in state repression, he co-founded and became leader of the ANC's armed wing, Umkhonto we Sizwe ("Spear of the Nation"). The group engaged in bombing campaigns against government and military buildings, while not harming any people. Mandela coordinated these campaigns and travelled abroad to raise funds for the group.

On 5th August 1962, the security police followed a CIA tip-off and arrested Mandela. He faced charges of inciting workers to strike and travelling abroad illegally for which he was found guilty and sentenced to five years imprisonment. Following the arrest of many leaders of the ANC in 1963, Mandela faced trial again on charges of sabotage and other treasonous activities. Found guilty he escaped the death penalty, but received a sentence of life imprisonment.

Robben Island became Mandela's home for eighteen of his twenty-seven years in prison. While there he engaged in hard labour in a lime quarry and also received a Bachelor of Laws degree from the University of London after studying by correspondence. Meanwhile he became a cause célèbre as international opinion turned against the South African government and their segregationist policies.

In 1982, the authorities relocated Mandela and the other ANC leaders to Pollsmoor Prison near Cape Town. Three years later Mandela met with a representative of the National Party government at the Volks Hospital in Cape Town where he was undergoing treatment on his prostate. Nevertheless, no progress was made until Frederik Willem de Klerk became president in August 1989.

The following February de Clerk lifted the ban on the ANC and the other anti-apartheid organisations and announced the imminent release of Nelson Mandela. On 11th February 1990, millions of television viewers watched Nelson Mandela leave Victor Verster Prison in Paarl as a free man. He resumed his role as a leader of the ANC taking part in the four years of negotiations with the government.

In recognition of the attempts at peace and reconciliation the Nobel prize committee awarded Mandela and de Clerk with the Peace Prize in 1993. A year later the first South African multi-racial elections took place. The ANC received 62% of the vote and Mandela became the first black president of South Africa. He remained in office for five years becoming a world statesman, a position he still holds.

BBC News footage of Mandela's release

Related posts

Foundation of the African National Congress: 8th January 1912

Southern Rhodesians chose not to join the Union of South Africa: 27th October 1922

Swaziland became independent: 6th September 1968

10 February 2011

On this day in history: Treaty of Paris signed, 1763

In 1756, Empress Maria Theresa of Austria formed a new alliance with Russia and France in order to recover territories lost to Prussia during the War of Austrian Succession, particularly Silesia. Meanwhile, the British no longer felt that the Austrians could contain French power in Europe. So rather than remain allied with the Austrians they signed a pact with King Frederick II of Prussia in return for his protection of Hanover - the ancestral home of the British royal dynasty - from French aggression.

In 1756, Empress Maria Theresa of Austria formed a new alliance with Russia and France in order to recover territories lost to Prussia during the War of Austrian Succession, particularly Silesia. Meanwhile, the British no longer felt that the Austrians could contain French power in Europe. So rather than remain allied with the Austrians they signed a pact with King Frederick II of Prussia in return for his protection of Hanover - the ancestral home of the British royal dynasty - from French aggression.

Hostilities began when Frederick invaded Saxony, which was allied with the Austrians. The Austrians and their allies - France, Russia, Sardinia, Sweden and the Holy Roman Empire - declared war on Prussia, their German allies and Great Britain. While the Prussian army, which was the most formidable in Europe at that time, fought the Austrian alliance on land, the powerful British navy engaged the allies at sea.

To check British naval power in the Mediterranean, the French captured the British owned island of Minorca. War soon spread around the globe as British and French colonists fought in Africa, Asia and particularly in North America where they had been skirmishing for years. The deployment of British land forces to their colonies resulted in them making substantial gains at the expense of the French expanding their empire around the world.

In Europe, Portugal entered the fray on the side of the British and Prussians, and Spain joined the Austrian alliance. A series of Prussian defeats brought Frederick to the brink of disaster, especially when the British threatened to withdraw their financial aid. Fortunately for him, in 1762 the Russian Empress Elizabeth died. Her successor, Peter III , who was more friendly to the Prussians immediately withdrew his troops from the war and helped negotiate a peace between Frederick and the Swedes. Having lost an important ally and facing a reverse of fortunes on the battlefield, the Austrians had little choice but to negotiate a peace.

War weariness in Britain contributed to King George III's removal of the Duke of Newcastle's government and the resultant peace negotiations with France. On 10th February 1763, representatives of France, Great Britain, Spain and Portugal signed the Treaty of Paris, ending the conflict that is known as the Seven Years War in Europe, and the French and Indian War in America. The Treaty required a complex exchange of territories between the powers. The French had the choice of keeping either New France (Canada) or Guadeloupe in the Caribbean. They chose to keep the latter as a supply of sugar, but they also had to return Minorca to the British. The British also gained Florida from the Spanish, who received New Orleans and the western part of Louisiana from the French.

The text of the "Treaty of Paris (1763)" is available on the Yale Law School's Avalon Project web site.

Related posts

British Parliament expelled John Wilkes: 19th January 1764

Execution of Admiral Byng: 14th March 1757

Battle of Leuthen: 5th December 1757

Louisiana Purchase Treaty signed: 30th April 1803

9 February 2011

On this day in history: Maiden flight of Boeing 747, 1969

With long-distance commercial air travel becoming more popular the President of Pan American World Airways (Pan Am), Juan Trippe, urged Boeing to build a much larger passenger aircraft to replace the successful 707 and alleviate traffic congestion at airports. In 1965 Boeing engineer Joe Sutter took control of a development team, which liaised with Pan Am and other airlines to design an aircraft that would meet their requirements. The result was the 747, an aircraft that could be easily adapted to become a freight carrier when the expected supersonic air travel revolution took place.

With long-distance commercial air travel becoming more popular the President of Pan American World Airways (Pan Am), Juan Trippe, urged Boeing to build a much larger passenger aircraft to replace the successful 707 and alleviate traffic congestion at airports. In 1965 Boeing engineer Joe Sutter took control of a development team, which liaised with Pan Am and other airlines to design an aircraft that would meet their requirements. The result was the 747, an aircraft that could be easily adapted to become a freight carrier when the expected supersonic air travel revolution took place.

In April 1966, Pan Am became the first of twenty-six airlines to pre-order 747s, which Boeing undertook to start delivering be the end of the decade. Pan Am again partnered Boeing along with Pratt and Whitney in the design of a new turbofan engine that would produce enough power for the enormous airliner. In spite of the limited development time, the first prototype 747 rolled out of Boeing's purpose-built assembly plant at Paine Field near Everett, Washington, on 30th September 1968.

On 9th February 1969, the first air-worthy prototype called City of Everett made its maiden flight. The flight crew comprised test pilots Jack Waddell and Brien Wygle, and flight engineer Jess Wallick. Apart from a minor fault with one of the flaps the crew reported that the aircraft handled extremely well in flight.

Flight tests continued for the next few months during which time the engineers ironed out any problems, particularly with the engines. On 15th January 1970 Pan Am took possession of the first production 747s that entered service between New York and London a week later. Over the next forty years development continued on the 747 with Boeing manufacturing a number of variants for carrying cargo as well as passengers, including the President of the United States, and even giving a piggy-back to the prototype Space Shuttle.

Related posts

First Zeppelin flight: 2nd July 1900

First successful powered aeroplane flight: 17th December 1903

Last commercial Concorde flights: 24th October 2003

8 February 2011

On this day in history: Appearance of the Devil`s Footrpints, 1855

On the night of 8th/9th February 1855, a series of mysterious footprints appeared in freshly fallen snow. The Times of February 16th reported the 'Extraordinary Occurrence' in the following article:

Considerable sensation has been caused in the towns of Topham, Lympstone, Exmouth, Teignmouth, and Dawlish, in the south of Devon, in the consequence of the discovery of a vast number of foot-tracks of a most strange and mysterious description. The superstitious go so far as to believe that they are the marks of Satan himself; and that great excitement has been produced among all classes may be judged of from the fact that the subject has been descanted on from the pulpit. It appears that, on Thursday night last, there was a very heavy fall of snow in the neighbourhood of Exeter and the south of Devon. On the following morning the inhabitants of the above towns were surprised at discovering the foot-marks of some strange and mysterious animal, endowed with the power of ubiquity, as the footprints were to be seen in all kinds of unaccountable places - on the tops of houses and narrow walls, in gardens and courtyards, enclosed by high walls and palings, as well as in open fields. There was hardly a garden in Lympstone where these footprints were not observable. The track appeared more like that of a biped than a quadruped, and the steps were generally eight inches in advance of each other. The impression of the foot closely resembled that of a donkey's shoe, and measured from an inch and a half to (in some instances) two and a half inches across. Here and there it appears as if cloven, but in the generality of the steps the shoe was continuous, and from the snow in the centre remaining entire, merely showing the outer crest of the foot, it must have been convex. The creature seems to have approached the doors of several houses and then to have retreated, but no one has been able to discover the standing or resting point of the mysterious visitor. On Sunday last the Rev. Mr. Musgrave alluded to the subject in his sermon, and suggested the possibility of the footprints being those of a kangaroo; but this could scarcely have been the case, as they were found on both sides of the estuary of the Exe. At present it remains a mystery, and many superstitious people in the above towns are actually afraid to go outside of their doors after night.

The Times (16th February 1855), p. 8.

7 February 2011

On this day in history: New South Wales founded, 1788

In August 1770 the English mariner and explorer James Cook (then a lieutenant) took possession of the eastern coast of Australia in the name of King George III, naming it New South Wales. Apart from a flag planted by Cook on Possession Island in the Torres Straight there was little evidence of the British claim over eastern Australia until the arrival of the First Fleet under Captain Arthur Phillip. The Home Secretary, Lord Sydney, had charged Phillip with the governorship of a new penal colony to be established at Botany Bay. The fleet of eleven ships set sail in May 1787 carrying 772 convicts (both men and women), most of whom were petty thieves from London, and a small contingent of marines and naval officers.

In August 1770 the English mariner and explorer James Cook (then a lieutenant) took possession of the eastern coast of Australia in the name of King George III, naming it New South Wales. Apart from a flag planted by Cook on Possession Island in the Torres Straight there was little evidence of the British claim over eastern Australia until the arrival of the First Fleet under Captain Arthur Phillip. The Home Secretary, Lord Sydney, had charged Phillip with the governorship of a new penal colony to be established at Botany Bay. The fleet of eleven ships set sail in May 1787 carrying 772 convicts (both men and women), most of whom were petty thieves from London, and a small contingent of marines and naval officers.

Reaching Botany Bay in January 1788, Philip found it to be inadequate for his purposes and decided to land the troops and convicts at Sydney Cove, which he named after the Home Secretary, on the southern shore of Port Jackson. On 7th February 1788 Philip assumed the title of Governor of New South Wales formally founding the first British settlement in Australia. Eight days later he established the first colony at Port Jackson and soon after sent a small detachment of men to create a second colony at Norfolk Island both as an alternative food source and to prevent the French from taking possession of it.

Life in the colonies was harsh and chaotic at first. The marines were often nearly as ill-disciplined as the convicts and Philip soon began appointing some convicts as overseers who forced the others to work. The Governor also established friendly relations with the local indigenous population, the Cadigal, who were nevertheless ravaged by diseases the British had brought.

Within a couple of years Philip managed to create a stable settlement with a population of around two thousand. One convict called James Ruse asked for land to establish a farm. When Ruse made a success of an allotment Philip granted him ownership of thirty acres of land inspiring other convicts to follow suit.

Largely forgotten by Britain, Philip continued to administer the colony until ill-health forced him to request permission to return home. He received permission to do so and set sail in December 1792. He left behind him a successful settlement of over four-thousand people.

Project Gutenberg hosts electronic copies of Arthur Phillip's book The Voyage of Governor Phillip to Botany Bay With an Account of the Establishment of the Colonies of Port Jackson and Norfolk Island (1789).

Related posts

First English colony in North America founded: 5th August 1583

Foundation of first permanent British colony in the Caribbean: 28th January 1624

First university inaugurated in Australia: 11th October 1852

6 February 2011

Link to The Modern Historian

If you wish to link to The Modern Historian, copy the following code and paste it into your website's html file or add it to your blog. Please leave a comment if you need any help doing this, or if you have a history based site and wish me to add you to my links list.

5 February 2011

On this day in history: BBC Radio first broadcast the Greenwich Time Signal, 1924

From its first broadcasts, the British Broadcasting Company (BBC) included a time check before their evening news bulletins taking the form of the chimes of Big Ben being played originally on a piano and later on tubular bells. The research department at Marconi suggested that a time signal under the control of the Royal Observatory in Greenwich might be broadcast but the BBC chose to use synchronised clocks. During a radio broadcast in April 1923 the horologist Frank Hope-Jones again mooted the idea of the BBC broadcasting a more accurate time signal in the form of a series of 'pips.' In December 1923, the General Manager of the BBC, Lord Reith, and the Astronomer Royal, Sir Frank Dyson, agreed on a plan to modify two clocks at the Royal Observatory to produce a signal that the BBC could broadcast.

From its first broadcasts, the British Broadcasting Company (BBC) included a time check before their evening news bulletins taking the form of the chimes of Big Ben being played originally on a piano and later on tubular bells. The research department at Marconi suggested that a time signal under the control of the Royal Observatory in Greenwich might be broadcast but the BBC chose to use synchronised clocks. During a radio broadcast in April 1923 the horologist Frank Hope-Jones again mooted the idea of the BBC broadcasting a more accurate time signal in the form of a series of 'pips.' In December 1923, the General Manager of the BBC, Lord Reith, and the Astronomer Royal, Sir Frank Dyson, agreed on a plan to modify two clocks at the Royal Observatory to produce a signal that the BBC could broadcast.

The system produced a series of six short five seconds before the end of the hour with the last one generated on the stroke of the hour or half-hour. GPO phone cables carried this signal to the BBC where it was converted to an audible signal. At 9.30pm on 5th February 1924 the BBC broadcast the first Greenwich Time Signal, soon to be known as 'the pips,' following an introduction from the Astronomer Royal.

Related posts

Foundation stone of Royal Greenwich Observatory laid: 10th August 1675

First live radio broadcast of a soccer match: 22nd January 1927

BBC Television Service started broadcasting: 2nd November 1936

First commercial transistor radio announced: 18th October 1954

4 February 2011

On this day in history: Disney`s Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs released, 1938

In June 1934, Walt Disney announced the production of his studio's first feature length animation: Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs. Previously the Disney studio had released short films such as those in the Mickey Mouse series. Disney's family tried to dissuade him from the venture, while other industry insiders referred to the moving picture as "Disney's Folly."

In June 1934, Walt Disney announced the production of his studio's first feature length animation: Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs. Previously the Disney studio had released short films such as those in the Mickey Mouse series. Disney's family tried to dissuade him from the venture, while other industry insiders referred to the moving picture as "Disney's Folly."

Production of Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs had begun earlier that year with a team of writers adapting the original story written by the Brothers Grimm. Frank Churchill (music) and Larry Morey (lyrics) wrote the songs for the movie, while Paul J. Smith and Leigh Harline scored the incidental music. David Hand headed the directorial team having worked for Disney studios since 1930, first as an animator and later as animation director.

Disney chose Adriana Caselotti to play the role of Snow White, then later blacklisted the singer from appearing elsewhere so as not to spoil the magic of Snow White. Lucille La Verne voiced the Queen, eventually doing so without her false teeth to get the voice just right. The voice of Goofy, Pinto Colvig, provided the voices of two of the dwarfs: Grumpy and Sleepy.

Production took three years with costs spiralling from Disney's original budget of $250,000 (ten times more than his animated shorts cost) to nigh on $1,500,000. To continue funding production Disney had to mortgage his own home. Eventually, on 21st December 21 1937 Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs premièred at the Carthay Circle Theater, Los Angeles to a rapturous reception.

On 4th February 1938 the movie went on general release grossing $66,596,803, a record amount. Snow White was the first full length animated feature requiring the development of many new techniques for which the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences awarded Disney with a special Oscar (and seven smaller ones). Snow White was also the first American movie to have a soundtrack album released simultaneously.

Related posts

First science fiction film released: 1st September 1902

Alfred Hitchcock died: 29th April 1980

3 February 2011

On this day in history: First banknotes issued in America, 1690

On 3rd February 1690, the Massachusetts Bay Colony legislature issued $40,000 worth of Bills of Credit. The British King authorised the Massachusetts General Court to issue these promissory notes to pay the army it had raised to fight against the French in Canada during King William's War, since it was short of official coinage at that time. Recipients of the notes could later redeem them for coins to the value of the issued note.

On 3rd February 1690, the Massachusetts Bay Colony legislature issued $40,000 worth of Bills of Credit. The British King authorised the Massachusetts General Court to issue these promissory notes to pay the army it had raised to fight against the French in Canada during King William's War, since it was short of official coinage at that time. Recipients of the notes could later redeem them for coins to the value of the issued note.

Each note read:

This indented Bill of [...] Shillings due from the Massachusetts Colony to the Possessor shall be in value equal to money and shall be accordingly accepted by the Treasurer and Receiver Subordinates to him in all Public payments and for any stock at any time in the Treasury - New England, February the third, 1690. By order of the General Court.

The notes proved a great success, soon entering general circulation.

The legislators spotted the potential of paper money and started issuing more notes not only during emergencies but also to cover the cost of general administration. The other New England colonies soon followed suit, issuing their own banknotes with mixed results. A shortage of gold and silver meant that the notes were rarely redeemed; yet, the authorities continued to print more notes resulting in their devaluation.

Related posts

First European banknotes: 16th July 1661

The United States Mint established: 2nd April 1792

U.S. Congress authorised Two-Cent coin: 22nd April 1864

First electronic Automatic Teller Machine installed: 27th June 1967

1 February 2011

On this day in history: First part of the Oxford English Dictionary published, 1884

On 1st February 1884 the Oxford University Press (OUP) published the first part of A New English Dictionary on Historical Principles; Founded Mainly on the Materials Collected by The Philological Society. The 352 page fascicle had 352 pages containing words from A to Ant, costing 12s.6d. Over the next forty-four years 125 fascicles were published to form the first edition of the Oxford English Dictionary (OED).

On 1st February 1884 the Oxford University Press (OUP) published the first part of A New English Dictionary on Historical Principles; Founded Mainly on the Materials Collected by The Philological Society. The 352 page fascicle had 352 pages containing words from A to Ant, costing 12s.6d. Over the next forty-four years 125 fascicles were published to form the first edition of the Oxford English Dictionary (OED).

The dictionary originated in June 1857 when three members of the Philological Society - Herbert Coleridge, and Frederick Furnivall, and Richard Chenevix Trench - formed an Unregistered Words Committee to identify words missing from existing dictionaries. The following year the society decided to produce a comprehensive dictionary of English words, based on quotations taken from printed works. The society allocated books to volunteers who would produce quotation slips that illustrated the usage of particular words.

Coleridge became the first editor in 1860. When he died the following year, he had received around 100,000 quotation slips. Furnivall took over as editor before recruiting James Murray as his successor in 1879. Furnivall and Murray met with a number of publishers before finally securing an agreement with the OUP in 1879, which published the first fascicle five years later.

In 1895, the title Oxford English Dictionary first appeared on the outer covers of the fascicles. Following the publication of the final fascicle on 19th April 1928, the OUP published the entire Dictionary in bound volumes. The OUP published a second edition in 1989, and is currently working on a third.

To learn more, visit the Dictionary's web pages, which include a History of the OED.

Related posts

Samuel Johnson`s Dictionary published: 15th April 1755

First edition of Encyclopædia Britannica published, 6th December 1768

First edition of The Times published, 1st January 1785