In February, 1873 King Amadeo I abdicated from the Spanish throne. Three years earlier, following the revolution against Queen Isabella II, the Spanish parliament, the Cortes Generales, had elected Amadeo , an Italian prince, as King to reign as a constitutional monarch. Political infighting within the Cortes hampered his ability to respond to successive disasters: uprisings in support of the restoration of the Bourbon dynasty, known as Carlists; republican revolts; and even assassination attempts. Amadeo finally gave up and returned to Italy as the Duke of Aosta, after the increasingly radical government forced him to sign a decree to sack a group of artillery officers who had refused to take orders from their new commander.

In February, 1873 King Amadeo I abdicated from the Spanish throne. Three years earlier, following the revolution against Queen Isabella II, the Spanish parliament, the Cortes Generales, had elected Amadeo , an Italian prince, as King to reign as a constitutional monarch. Political infighting within the Cortes hampered his ability to respond to successive disasters: uprisings in support of the restoration of the Bourbon dynasty, known as Carlists; republican revolts; and even assassination attempts. Amadeo finally gave up and returned to Italy as the Duke of Aosta, after the increasingly radical government forced him to sign a decree to sack a group of artillery officers who had refused to take orders from their new commander.

The day after the abdication, the Cortes voted that Spain become a republic but could not agree on what form it should take, some preferred that Spain become a federation while others wanted a unitary republic. The divisions in Spanish society undermined the republic as they had done with the constitutional monarchy. In January, 1874 the Captain General of Madrid, Manuel Pavía, declared his opposition to the federalism, which resulted in the formation of a unitary government without the federalists and monarchists.

With the Cortes disbanded the fate of the nation rested in the hands of the military forces of the various factions. The republican army managed to reverse the territorial gains made by the Carlists before deciding not to oppose Brigadier Martínez Campos when he declared his support for the Bourbon Prince Alfonso, son of Isabella, on 29th December 1874. Having lost control of their armed forces the government of the first republic collapsed, paving the way for the restoration of the Bourbon monarchy.

Customised search for historical information

29 December 2008

On this day in history: First Spanish Republic ended, 1874

20 December 2008

On this day in history: Electricity generated by nuclear power for the first time, 1951

In 1934 the Italian physicist Enrico Fermi produced nuclear fission for the first time for which he received the Nobel Prize for Physics four years later. After receiving his prize, Fermi emigrated to the United States with his Jewish wife Laura to escape Mussolini's increasingly anti-semitic fascist regime in his homeland. He worked at Columbia University where he continued experimenting on nuclear fission before joining the project at the University of Chicago constructing the world's first nuclear reactor.

In 1934 the Italian physicist Enrico Fermi produced nuclear fission for the first time for which he received the Nobel Prize for Physics four years later. After receiving his prize, Fermi emigrated to the United States with his Jewish wife Laura to escape Mussolini's increasingly anti-semitic fascist regime in his homeland. He worked at Columbia University where he continued experimenting on nuclear fission before joining the project at the University of Chicago constructing the world's first nuclear reactor.

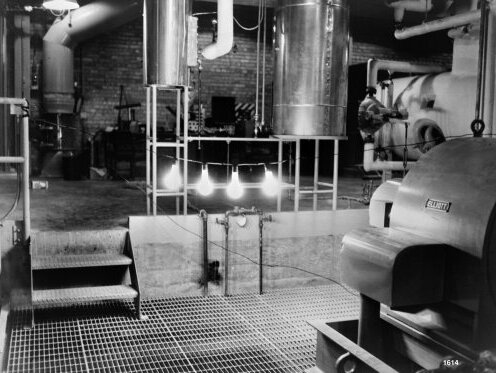

Following America's entry into the Second World War, the experimental work conducted on Chicago Pile-1 became part of the Manhattan Project, which was engaged in creating nuclear weapons. Following the end of the war, development began on more peaceful applications of reactor research, including the generation of electricity. To this end the United States government established the National Reactor Testing Station (NRTS) - now called the Idaho National Laboratory - in the Idaho desert in 1949.

That year construction work began on the Experimental Breeder Reactor 1 (EBR-1) at NRTS. Walter Zinn, who had also worked on the Manhattan Project, and his team at the Argonne National Laboratory designed EBR-1 as an attempt to prove that it was possible to create a breeder reactor rather than to become a working power plant. A breeder reactor is one that creates nuclear fuel at a rate that is greater than it can consume it.

On 24th August 1951 the reactor went critical for the first time. At 1:50pm on 20th December 1951, the power station produced electricity for the first time. It generated enough electricity to illuminate four 200watt light bulbs. The next day the scientists repeated the experiment, producing enough electricity for the EBR-1 building.

Two years later, it successfully began producing fuel as a breeder reactor. Experiments continued on the EBR-1, even after the reactor suffered a partial meltdown in November 1955, until it was deactivated in 1964. The following year EBR-1 became a National Historic Landmark.

To learn more about the reactor see the Experimental Breeder Reactor 1 fact-sheet available as a pdf file from the Idaho National Laboratory site.

19 December 2008

On this day in history: Emily Brontë died, 1848

Born on 30th July 1818 at the Parsonage in Thornton, near Bradford, Yorkshire, Emily Jane Brontë was the fifth of six children of Revd. Patrick Brontë and his wife Maria. Nearly two years after her birth, Emily's family moved to the small industrial town of Haworth where her father had accepted the post of curate, which offered greater financial security. Unfortunately, a year and a half after the family relocated, Maria died.

Born on 30th July 1818 at the Parsonage in Thornton, near Bradford, Yorkshire, Emily Jane Brontë was the fifth of six children of Revd. Patrick Brontë and his wife Maria. Nearly two years after her birth, Emily's family moved to the small industrial town of Haworth where her father had accepted the post of curate, which offered greater financial security. Unfortunately, a year and a half after the family relocated, Maria died.

Their mother's older sister Elizabeth Branwell stayed on with the family after nursing Maria during the last months of her life. While the older Brontë girls clashed with their aunt when she extolled the virtues of fastidiousness and self-discipline, Emily did not. As well as learning domestic skills the girls also received instruction in more academic subjects along with their brother Branwell.

The four oldest girls were sent to the Clergy Daughters' School at Cowan Bridge, a newly founded institution that provided a formal education to the daughters of less wealthy Anglican clergymen. The poor conditions at Cowan Bridge resulted in a number of pupils contracting illnesses, including Emily's oldest two sisters, Maria and Elizabeth, both of whom contracted tuberculosis, wcich caused their deaths in 1825. Revd. Brontë brought Emily and her sister Charlotte home where he and Miss Branwell continued to educate them.

The four remaining siblings became a close-knit group, developing imaginary worlds that they began writing about. The four were separated when Charlotte attended Roe Head school in Mirfield. She later returned as a teacher there accompanied by Emily who went there as a pupil. After only three months Emily became so ill that she had to return home to be replaced at Roe Head by her sister Anne.

Divided from her sister Anne, with whom she was closest, Emily became more self-reliant and remained apart from the rest of her family. Much of her time was spent secretly writing poetry until she took the position of teacher at Law Hill girl's school near Halifax in 1838. She remained there for six months before another illness required that she return to Haworth.

Charlotte had the idea of setting up a school and persuaded their aunt to pay for her and Emily to attend a school in Brussels. Emily struggled through nine months of being the oldest pupil in a school where lessons were taught in French - a language she was not well versed in - before her father summoned her and Charlotte home because of the death of their aunt.

In 1845, Charlotte discovered one of Emily's poetry books, much to the annoyance of the younger sister. In spite of Emily's anger, the other Brontë children persuaded her to allow them to select poems to be submitted for publication along with other poems written by her sisters. A year later two girls published the collection called Poems pseudonyms of Currer, Ellis, and Acton Bell (Charlotte, Emily and Anne respectively).

Two years later, Emily, again under the name Ellis Bell, published the work for which she became famous: Wuthering Heights. This epic tale of the Earnshaws of Wuthering Heights and the Lintons of Thrushcross Grange confounded the critics of the day because of its innovative style. The publishers demanded that Emily contribute towards the publishing costs, even though they were using the Bell name to cash in on the success of Jane Eyre, written by Charlotte under the name Currer Bell.

The following year, Emily's brother Branwell died of tuberculosis - the symptoms of which had been masked by his alcoholism. At his funeral Emily contracted a cold that resulted in her own death on 18th December 1848. Following her death, Charlotte edited the two part Wuthering Heights into a single volume that was published under her real name.

The Project Gutenberg site hosts Poems and Wuthering Heights as well as other works by the Brontës.

18 December 2008

On this day in history: First European landing on New Zealand, 1642

Born in 1603 in the Dutch province of Groningen, Abel Tasman entered the service of the Vereenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie (Dutch East India Company). By the mid-1630s Tasman was serving as a mate on a trading ship out of Batavia (modern day Jakarta). In 1634 he became master of the Mocha, a small trading ship, and served as second in command on a mission of exploration of the North Pacific.

Born in 1603 in the Dutch province of Groningen, Abel Tasman entered the service of the Vereenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie (Dutch East India Company). By the mid-1630s Tasman was serving as a mate on a trading ship out of Batavia (modern day Jakarta). In 1634 he became master of the Mocha, a small trading ship, and served as second in command on a mission of exploration of the North Pacific.

After a series of journeys to various locations on the Pacific coast of Asia, Tasman commanded a fleet sent to search for the "Unknown Southland and Eastland" believed to be in the South Atlantic. In August 1642 he set sail for Mauritius where he turned south-east for then little known Australia. In November he sighted the island that now bears his name, which he claimed for the Netherlands on 3rd December.

Tasman intended to turn north to explore the east coast of Australia, but strong winds took the fleet on an easterly heading. On 13th December the explorers sighted land: the north-west coast of the Southern Island of what is now known as New Zealand. While exploring the coast, the fleet had a number of encounters with the Maori including an attack on one of the Dutch ships, which goes some way to explaining why the fleet only made a brief landing on the 18th December.

The fleet continued to explore the islands before returning to Batavia via the Tongan and the Fiji islands. Tasman made another voyage of discovery in 1644 before becoming a senior official in Batavia. He continued to serve there until his death in October 1659, apart from a period of suspension as a result of him passing a death sentence on a man without trial.

Abel Janszoon Tasman's Journal of his Discovery of Van Diemen's Land and New Zealand in 1642 is available on the Project Gutenberg Australia site.

17 December 2008

On this day in history: First successful powered aeroplane flight, 1903

At the dawn of the twentieth-century, the brothers Orville and Wilbur Wright left their cycle manufacturing business in Dayton, Ohio and travelled to Kitty Hawk, North Carolina to undertake experiments with flying machines. Over the next few years they made their annual pilgrimage to the sands of Kitty Hawk to refine the design of their manned gliders. Following successful test flights in the 1902 Glider, the brothers added an engine designed and built by one of their employees, Charlie Taylor, to their next model: the Wright Flyer I.

At the dawn of the twentieth-century, the brothers Orville and Wilbur Wright left their cycle manufacturing business in Dayton, Ohio and travelled to Kitty Hawk, North Carolina to undertake experiments with flying machines. Over the next few years they made their annual pilgrimage to the sands of Kitty Hawk to refine the design of their manned gliders. Following successful test flights in the 1902 Glider, the brothers added an engine designed and built by one of their employees, Charlie Taylor, to their next model: the Wright Flyer I.

In December 1903, the brothers returned to North Carolina and assembled the Flyer while performing flight tests with the 1902 Glider. On the 14th, the brothers tossed a coin to decide which of them should pilot the Flyer for its maiden flight. Wilbur won, but he stalled the plane after pulling up too sharply.

Fortunately the aircraft did not suffer any major damage and was ready for another test flight within days. On 17th December 1903, Orville took his chance to make history. The flight lasted for twelve seconds in which time he covered a distance of 36.5m (120 feet). According to the Fédération Aéronautique Internationale this was the World's first "sustained and controlled heavier-than-air powered flight."

The Smithsonian Institution refused to recognise the Wright's flight, preferring to give the accolade to one of their former secretaries, Samuel Pierpont Langley. Following Orville's unsuccessful attempt blackmail the Smithsonian into recognising the Wright's achievement by threatening to allow another museum to have the Flyer, the aircraft become an exhibit at the Science Museum in London, in 1928. Fifteen years later, Orville allowed the aircraft to be relocated to the Smithsonian after he received assurances that no other successful flight will be recognised by the Institution on a date prior to that of the brothers.

To learn more about these pioneering auronauts and their aircraft, see the Wright Experience site.

16 December 2008

On this day in history: Last recorded eruption of Mount Fuji, 1707

On 16th December 1707, Mount Fuji in Japan erupted. While this Hōei Eruption (as it became known) did not produce a lava flow, during its two week duration the eruption sporadically released hundreds of millions of cubic metres of volcanic ash into the atmosphere. This ash fell like rain on the nearby provinces of Izu, Kai, Musashi and Sagami, and witnesses recorded ash falling on Edo nearly 100km (60miles) away.

On 16th December 1707, Mount Fuji in Japan erupted. While this Hōei Eruption (as it became known) did not produce a lava flow, during its two week duration the eruption sporadically released hundreds of millions of cubic metres of volcanic ash into the atmosphere. This ash fell like rain on the nearby provinces of Izu, Kai, Musashi and Sagami, and witnesses recorded ash falling on Edo nearly 100km (60miles) away.

The eruption resulted in the opening of three new vents on the easterly side of the mountain and a small crater formed by a secondary eruption. Over the next year many effects of the eruption were felt including a flood of the Sakawa river caused by the fallen ash adding to the existing sediment in the riverbed. Mount Fuji has not erupted since Hōei, although it has yet to be declared inactive.

15 December 2008

Award and return

I would like to start by thanking Fashiona and Cindy at the Fenced in Family Blog for bestowing the Butterfly Award on the Modern Historian.

The rules for this award are:

1. Put the logo on your blog.

2. Add a link to the person who awarded you.

3. Nominate 10 other blogs.

4. Add links to those blogs on yours.

5. Leave a message for your nominees on their blogs

As such would like to pass on the award-love to the following:

A Brood Comb

Blogger-Aid

Blogger Buster

EleanorBlog

Geek Mom Mashup

Learn French

Let's Learn French Together

Streamlined Mind

The Midnight Flyer

The Mythogenetic Grove

I am also glad to announce that the "On this day in history" posts will appear again soon, now that I have finished my assignment.