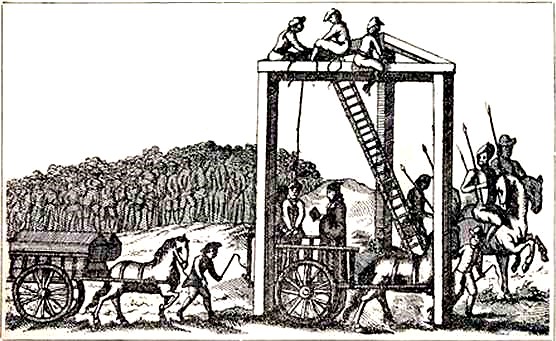

In February, 1873 King Amadeo I abdicated from the Spanish throne. Three years earlier, following the revolution against Queen Isabella II, the Spanish parliament, the Cortes Generales, had elected Amadeo , an Italian prince, as King to reign as a constitutional monarch. Political infighting within the Cortes hampered his ability to respond to successive disasters: uprisings in support of the restoration of the Bourbon dynasty, known as Carlists; republican revolts; and even assassination attempts. Amadeo finally gave up and returned to Italy as the Duke of Aosta, after the increasingly radical government forced him to sign a decree to sack a group of artillery officers who had refused to take orders from their new commander.

In February, 1873 King Amadeo I abdicated from the Spanish throne. Three years earlier, following the revolution against Queen Isabella II, the Spanish parliament, the Cortes Generales, had elected Amadeo , an Italian prince, as King to reign as a constitutional monarch. Political infighting within the Cortes hampered his ability to respond to successive disasters: uprisings in support of the restoration of the Bourbon dynasty, known as Carlists; republican revolts; and even assassination attempts. Amadeo finally gave up and returned to Italy as the Duke of Aosta, after the increasingly radical government forced him to sign a decree to sack a group of artillery officers who had refused to take orders from their new commander.The day after the abdication, the Cortes voted that Spain become a republic but could not agree on what form it should take, some preferred that Spain become a federation while others wanted a unitary republic. The divisions in Spanish society undermined the republic as they had done with the constitutional monarchy. In January, 1874 the Captain General of Madrid, Manuel Pavía, declared his opposition to the federalism, which resulted in the formation of a unitary government without the federalists and monarchists.

With the Cortes disbanded the fate of the nation rested in the hands of the military forces of the various factions. The republican army managed to reverse the territorial gains made by the Carlists before deciding not to oppose Brigadier Martínez Campos when he declared his support for the Bourbon Prince Alfonso, son of Isabella, on 29th December 1874. Having lost control of their armed forces the government of the first republic collapsed, paving the way for the restoration of the Bourbon monarchy.